Pharmacists have huge potential in the refugee crisis but must act now

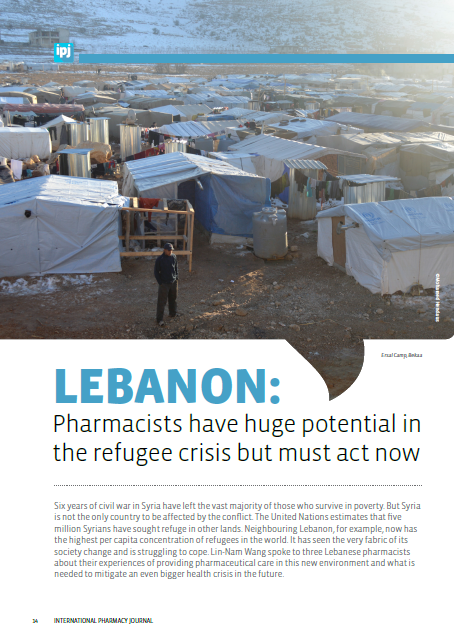

Six years of civil war in Syria have left the vast majority of those who survive in poverty. But Syria is not the only country to be affected by the conflict. The United Nations estimates that five million Syrians have sought refuge in other lands. Neighbouring Lebanon, for example, now has the highest per capita concentration of refugees in the world. It has seen the very fabric of its society change and is struggling to cope. Lin-Nam Wang spoke to three Lebanese pharmacists about their experiences of providing pharmaceutical care in this new environment and what is needed to mitigate an even bigger health crisis in the future.

Racha Mourtada, Aline Fraiha and Mohamed Hendaus are all young pharmacists living and working in the Bekaa Valley, which has become home to many Syrian refugees. “Our population of 4.3 million in Lebanon has seen a 30% increase, with one in four people being a refugee,” Ms Mourtada told IPJ. But in the Bekaa Valley, she said, the situation is even more acute, with about 70% of the population being Syrian. “The impact on health, our health care system and the way in which we practise has been huge, and day by day this crisis is becoming a bigger problem,” she said.

In the pharmacy where Ms Mourtada works, which is near a camp, 90% of the customers are refugees. Since many of the refugees cannot afford to see a doctor, they are turning to pharmacists for help because they are accessible, she explained. The Lebanese health system relies heavily on the private sector. Funding for refugee health care is provided by the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the European Commission, but not all treatments and services are covered. Moreover, according to the European Commission, refugees are scattered in more than 1,700 localities across the country. The distribution of aid is unequal, with some areas benefiting and others not, Ms Mourtada said.

“Feeding and settling are priorities over hygiene and health, but this all makes for massive consequences in the future.”

Pharmacists are encountering difficulties helping these patients. Although both Lebanese and Syrians speak Arabic, there is a difference in accent, which leads to communication problems. The names of medicines are different and the refugees ask for medicines they have taken in their homeland, Ms Mourtada said. Moreover, there is a huge lack of health awareness, with growing illiteracy adding to the problem. People cannot afford even simple care, and feeding and settling are priorities over hygiene and health, but this all makes for massive consequences in the future, she said.

Birth control awareness

Lack of awareness of birth control among refugees is a particular concern, according to Ms Mourtada. She explained that in Syrian culture, women often marry when they are 15 or 16 years of age and it is not uncommon for them to have six or seven children. “Some of them think that if they have lots of children, they can help them with working, but they don’t understand that it is also their responsibility to provide good health care, including immunisations, for their children. I once asked a mother of seven who was weak with anaemia if she knew she could use birth control. Her answer was that her husband had not told her,” she said.

Her belief is that if people understand that having smaller families will give them a better and healthier quality of life and a better chance to educate their children, this will improve things not just for them but for Lebanese society as a whole. “Having educated children would slow down demands on health care systems because people would understand how to stay healthy. Fewer illiterate children would also mean fewer people later turning to crime due to poverty. We should start with educating the younger children who don’t yet have a fixed mindset,” she said.

According to Ms Mourtada, there is a huge gap in the medicines supply for refugees, especially for chronic diseases, but also birth control. Only a few health centres are providing birth control free for refugees. The bulk of the problem lies in the limited quantities of medicines compared with the huge numbers in need. She believes that investment in providing birth control would benefit both the refugees and the host community.

Addiction and other mental health problems

Ms Fraiha’s first contact with a refugee changed her outlook forever. As a PharmD student performing triage in an emergency department, she encountered a 13-year-old rape victim, whose mother begged her for help. “I felt as if I had been living in a superficial world,” she told IPJ. At the time, the only way of helping that was open to her was to become a volunteer with a non-governmental organisation, going into camps as an observer. She talks to refugees, gathering information so that those in need can be referred for the help they need. This, she said, requires a different approach from the patient counselling skills she had learnt in pharmacy: “In pharmacy school, I was taught to talk to patients — people who already trust the pharmacist and are wanting advice — but the Syrian refugee needs to trust you as a person.” She elicits trust in a number of ways, ranging from wearing inexpensive clothes when she visits a camp to making sure that there are no men around if she wants to have a conversation with a woman. “I sometimes start a conversation simply by asking for some water to drink to show the person that you’re not afraid to drink their water,” she said.

Ms Fraiha’s voluntary work has made her even more aware of the refugees’ plight. “There are many mental health issues. The men are unable to find work and their frustration sometimes emerges in physical violence. Women frequently express suicidal thoughts to me,” she said. Addiction to fenetylline, tramadol and cough preparations is common.

The stimulant fenetylline (“Captagon”) is reported to be used to help the Syrian fighters keep going. “Initial use of tramadol may be as a cheap painkiller but people are taking them in large quantities from the black market,” Ms Fraiha said.

As well as presenting challenges to Lebanon’s health care system, the issue of addiction has revealed a number of inadequacies in the country’s infrastructure as well as problems within its pharmacy profession. “We have a big misunderstanding in our community. These people are called ‘asylum seekers’ and not ‘refugees’ and for that reason our government does not protect them,” Ms Fraiha said. She went on to explain that refugees with addiction problems have been approaching Lebanon’s Ministry of Social Affairs for help but are turned away, and that no NGO is providing addiction services. She added that, sadly, the Lebanese system means that too many pharmacists see the profession as a business and the supply of prescription-only medicines without a prescription is not well regulated, which leads to the sale of large quantities of tramadol and cough preparations in certain pharmacies.

According to Ms Fraiha, this is further facilitated by the fact that the country has no national pharmacy patient record system, although a system is currently being piloted by the president of the Lebanese Order of Pharmacists. “Pharmacists are turning a blind eye to addiction. Training and a change of mindset is needed. We do have a code of ethics but the humanistic part is missing. Colleagues need to understand that these people need our help. There is a lot that pharmacists could do here, such as increasing counselling when supplying medicines with addictive potential,” she added.

Pharmacists’ potential

Dr Hendaus’s work with refugees began early in the crisis. In 2011, as a pharmacy student, he joined a group of volunteers doing humanitarian work, which led him to visit many camps in Bekaa. It eventually influenced his choice of research for his PharmD: his thesis was on the role of Lebanese pharmacists as community health care professionals for Syrian refugees. His study showed that pharmacists could play a valuable part in raising awareness among refugees on hypertension through providing counselling, and he is planning further studies, such as exploring the role pharmacists can play in helping refugees with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Dr Hendaus believes pharmacists can play a vital role in refugee health, yet few go into camps. As far as he knows, only a few of the biggest camps that are controlled by NGOs have a pharmacist (mostly Syrian) and a mini-pharmacy. “It often means that no one is giving medicines advice [in camps]. There is no follow up on treatment. A patient might be given a box of medicine and not be given another,” he said. He described a situation in one camp where the person in charge, who had an education equivalent to a fifth or sixth grader, was keeping a “pharmacy” in his office. “When I asked how he was treating people with the medicines he kept, he said ‘I pick up the box, read the leaflet and act according to the age’,”

Dr Hendaus said. “Lack of health care practitioners inside the camps is the major challenge. For example, there is little help for bedridden patients,” he added. Ms Mourtada said that Lebanon has 9,000 pharmacists, of whom 2,000 are unemployed, and every year 400 more graduate. These could fill some of the workforce gaps but, she said, there is no strategy in place. She emphasised, however, that what is needed is pharmacists who really care about humanitarian issues.

Dr Hendaus also pointed out that efforts are being hampered by a lack of coordination among aid organisations as well as by a lack of resources in general. In terms of aid organisations, he said that there is no coordination between the mobile clinics; some camps might have five and others, none. Education is a major challenge in the refugee population, but pharmacists need to be educated too. “The crisis started in 2011, and this means that a child could have missed school for six or seven years; this will be even more significant later on, in terms of who is going to build Syria,” he explained. Poor living conditions and other related factors have led to the re-emergence of vector-borne diseases with which Lebanon’s pharmacists are unfamiliar, such as leishmaniasis and brucellosis, and to the exacerbation of endemic diseases such as tuberculosis and viral hepatitis. This has led the Ministry of Public Health to create a programme in Elias el Hrawi Public Hospital in Bekaa for the free treatment of leishmaniasis, and other programmes for the free treatment of TB, Mr Hendaus told IPJ. But many community pharmacists do not know to which institutions they can refer refugees who have such infections, he added. Among Dr Hendaus’s suggested relatively quick solutions would be to organise workshops on these emerging diseases and allow Lebanese pharmacists to earn some of their required 23 continuing education credits per year by visiting camps. A sort of guide map for pharmacists working near camps could also be developed so that they would know what services are available and to whom they can refer refugees.

Strategy and strength in numbers

As this crisis has taken its toll on Lebanon, resentment towards the refugees has grown and their situation has become political fodder for politicians, with Lebanese President Michel Aoun saying in September that he wants the refugees to be repatriated. But, Ms Mourtada said, “we really must remove ourselves from political issues. Our issue is humanitarian.” Ms Fraiha added: “This is not a temporary thing. In Lebanon these people have a safe place for their children. It could be 20 years before they will be able to return home. It’s a long-term problem facing us all.”

Dr Hendaus said: “I’ve lived in Bekaa since I was a child. I live with refugees every day. It really means a lot to me. I really want to deliver the message: the health of the refugees and the Lebanese are complementary.” They all agree that an “observe, assess and propose” strategy is needed. For example, they would like to create a survey for refugees that identifies levels of health awareness and healthy living practices in order to find out what awareness campaigns should be prioritised. “As pharmacists, we can do a lot. As first line health care professionals, we could implement such solutions and implement them quickly,” Ms Mourtada said.

All three are adamant that action is needed now to minimise problems down the line. But the many potential solutions are difficult to implement with only one voice or in an informal group. These three pharmacists have been brought together in their mission through the FIP network and are seeking like-minded pharmacists to join their Facebook group “PharmaHumanity”.