Nilhan Uzman, lead for education and primary healthcare policies, International Pharmaceutical Federation, The Netherlands

Alison Etukakpan, educational partnership specialist, International Pharmaceutical Federation, Nigeria

Dr Catherine Duggan, chief executive officer, International Pharmaceutical Federation, The Netherlands

Chapter 1 gives a background to inequities impacting pharmaceutical education through introductory video that sets the scene for equitable pharmaceutical education. There is an article discussing the reasons for addressing inequities in pharmaceutical education and its importance. Finally, the chapter ends with a series of interviews from global and regional stakeholders in education, giving their perspectives of different inequities impacting education in their regions and across the globe.

By Nilhan Uzman, lead for education and primary health care policies, International Pharmaceutical Federation, The Netherlands

In this introductory video to the toolkit, Ms Uzman gives a background to equitable pharmaceutical education linking FIP’s initiatives with those of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

By Prof. Ralph J. Altiere, chair of FIP Education, International Pharmaceutical Federation, USA

|

Key messages on why addressing inequities in education are important |

|

|

|

Inequities in education are closely linked with the inequities in opportunities to access education, lack of enabling public policies and social accountability and lack of progress in meeting the social determinants of health. |

|

|

Increasing access to pharmaceutical education, improving quality of teaching and learning, promoting effective leadership and establishing partnerships for education across the globe are key ways forward for addressing inequities in education. |

|

Pharmaceutical education must ensure that its internal environment is free from inequities that hinder our professional obligation to address SDOH and our social responsibility to achieve these goals. |

Overview

Inequity has been identified as one of the most serious issues in education worldwide and has multiple causes and consequences. Globally, these inequities correlate with the level of development of various countries and regions. This article discusses the inequity of opportunity, social accountability, social determinants of health, public policy, structural and systemic inequities in relation to FIP Development Goal 10 (Equity and equality) and inequities in pharmaceutical education. It projects an optimistic outlook for addressing inequities with evidence, and concludes by highlighting the reasons why pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences education programmes must address inequity.

Inequity of opportunity

Inequities in their many forms come down to one overriding inequity that appears to be the most harmful to society — the inequity of opportunity, which is the conduit through which inequality is reproduced between generations.1 Equality of opportunity has been a feature of Western politics since the 17th century and has continued until today. To quote the same reference: “In his 10 June 1936 address at Little Rock, Arkansas, for example, US President Franklin Roosevelt said, ‘We know that equality of individual ability has never existed and never will, but we do insist that equality of opportunity still must be sought.’ Likewise, the US philosopher John Rawls, in his highly influential 1971 treatise ‘A Theory of Justice’, reasoned that fair equality of opportunity — the idea that everyone in society should have the same access to goods, services and employment opportunities — is one of two principles of social justice.” We, obviously, have yet to reach this ideal. Inequity of opportunity underlies many ills of society, such as crime and health disparities, and has a negative impact on growth. Inequity of opportunity leads to inequitable access to education, and inequities in education lead to inequities of opportunity. Addressing inequities in education leads to greater opportunity.

Inequities, social accountability and social determinants of health

Inequities in pharmaceutical education are inextricably linked to social determinants of health and social accountability. The purpose of pharmacy and all health professional education is ultimately to reduce health disparities, improving health for all. But inequities in pharmaceutical education undercut this purpose. It is the primary reason why addressing inequities in pharmaceutical education now is so important.

Social accountability is based on the needs-based education model that has been a cornerstone of FIP Education for many years and remains as relevant today as ever.2 The purpose of social accountability is to ensure pharmaceutical education meets the health needs of communities locally, nationally and globally. Inequities in pharmaceutical education only serve to weaken this mission.

Inequities in pharmaceutical education closely track with social determinants of health (SDOH). The very causes for disparities in health care also are a basis, at least in part, for systemic and structural inequities in pharmaceutical education. SDOH have evolved since the WHO’s Global Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2008.3 The WHO originally defined SDOH as conditions or circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age that in turn are determined in large part by political, social and economic factors.4 Since then, many other factors have been added to the list. All these additions are legitimate, but at times they cause confusion or even resignation because there are too many factors to address to make a difference. Examples include education, living environment/housing, economic status, stress, early life, social support or exclusion, addiction, food security, transportation, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, disability status, stigma, discrimination, immigration status, racism, broadband internet service and, more recently, climate change and environmental threats.

Public policy, structural and systemic inequities

Underlying many, if not all, of the inequity factors is public policy.3 Public policies often reinforce structural and systemic inequities in education, health, employment, living conditions, and the ever-widening gap in income distribution (the 10 richest men in the world own more than the poorest 3.1 billion people).5-8 If pharmaceutical education is to address its internal inequities, it must look to these structural or systemic inequities. It will take advocacy and public policy change to correct them.

FIP equity and equality goal for pharmacy

FIP Development Goal 10 (Equity and equality) has a practice element, a science element and an education/workforce development element. The last has a focus on gender equity and equality.9 The education/workforce element may best be summarised in the FIP EquityRx Collection: “Achieving equity in health cannot be done without ensuring social accountability.”10

Social accountability as a concept is used in several contexts, including in health professional education, where it is defined as the obligation of training institutions to align their education, research and services to priority needs, and identify those needs in collaboration with stakeholders, including citizens. Social accountability is embedded within the WHO “Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030”, which aims to progress the health sustainable development goal and its workforce indicator. The APC [Australian Pharmacy Council] 2020 Accreditation Standards,11 effective since January 2020, provide a prime example of how social accountability can be embedded within health professional education. The standards consist of five main domains, the first of which — “Safe and socially accountable practice” — reflects the framing of the 2020 Accreditation Standards around the overarching principle of social accountability, which encompasses the responsibilities and obligations of individuals and organisations to serve society, by seeking both to prevent harm and to promote optimal health outcomes.

Inequities and pharmaceutical education

If pharmacy as a profession and the individuals within it meet their obligations to address SDOH and social accountability, we must educate students, practitioners and scientists in these matters, namely, what these determinants are, what our social contract entails and requires of us, and how to effectively address these health inequities. We cannot achieve these goals unless we identify and repair similar inequities in education. And we cannot fix these problems if we do not have the right people with the right knowledge and skills in our education institutions to lead the way. It is no small task to achieve these laudable goals. We must make reducing and, hopefully, removing inequities in pharmaceutical education a priority.12–15 We will learn how our colleagues are addressing at least several aspects of inequities in our schools in other chapters of the toolkit.

On the learner side is the inequitable opportunity to access pharmaceutical education, often the result of public policies. Perhaps the only apparently legitimate discriminatory factor in accessing pharmaceutical education is academic performance measures. Even these are flawed due to structural and other inequities within educational systems prior to reaching pharmacy school. We thereby limit the future academic pharmacy workforce in terms of the diversity of ideas and experiences needed to root out inequities in education, practice and science. Accordingly, as previously mentioned, we need to change public policy that underlies structural and systemic inequities that often go unrecognised. It is a tall order, but our toolkit authors will help to point us in the right direction.

Inequities can be overcome

Perhaps one of the more central reasons to address inequities in pharmaceutical education is because it is not an insurmountable problem. It can be fixed. We can make positive change. A few examples both internal and external to the world of pharmacy give us hope:

- Report of the Commission of the Pan American Health Organization on equity and health inequalities in the Americas: Just societies — Health equity and dignified lives.16 Health outcomes have improved dramatically across the Americas region but many people are left behind. This report lays out a pathway to reduce health inequities using examples of successful policies, programmes and actions along with recommendations to achieve greater health equity.

- How should physicians and pharmacists collaborate to motivate health equity in underserved communities?17 This article describes how pharmacists and physicians working together address SDOH and improve health outcomes.

- Hispanic students make huge gains in graduation.18 This news article describes impressive gains in graduation rates from Colorado, USA high schools by Hispanic students over a 10-year period (2010–20) in which graduation rates climbed from 55.5% to 74.5%. A multi-level approach — beginning with goal setting by policy makers and followed by monitoring school performance, reducing teen pregnancy rates, local school districts paying close attention to data to target supportive programmes at the right students, all actions related to addressing SDOH — demonstrated that through coordinated multifaceted efforts education inequities can be overcome. Although this example was in high schools, similar approaches from policy makers to school level individuals and programmes can correct inequities in pharmaceutical education.

- The COVID death rate for White Americans has recently exceeded the rates for Black, Latino and Asian Americans.19 This New York Times article from 9 June 2022 described how community-based, bottom-up programmes with intensive personal outreach efforts overcame many issues in Black, Latino and Asian American communities related to vaccine hesitancy and SDOH. The programmes yielded incredibly positive results in vaccination rates and declines in deaths from COVID-19 in 2021 to the extent that death rates among White Americans were 14% higher than for Black Americans and 72% higher than for Hispanic Americans in 2021. These outcomes are a complete reversal of what the death rates were for these groups prior to these community-based outreach efforts and demonstrate than health inequities and SDOH problems can be overcome. Similar efforts can and should be made to overcome inequities in pharmaceutical education.

Conclusions

If pharmaceutical education is to prepare future and current pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists to address inequities in health care and access to medicines, and achieve better health outcomes, pharmaceutical education must ensure that its internal environment is free from inequities that hinder our professional obligation for addressing SDOH and our social responsibility to achieve these goals. Doing so requires introspection and commitment to this priority to correct such inequities as much as possible.

Below is a list of expected results when education inequities in pharmaceutical education are addressed:

- Increases access to pharmaceutical education

- Generates stronger interest in medicines-related careers among those who previously did not have access

- Improves teaching and learning

- Places equity at the centre of the instructional model, so all learners benefit

- Shares leadership with other providers and clients of our services

- Ensures social accountability of educational programmes

- Effectively addresses social determinants of health to reduce health inequities

- Partners with the health care sector

- Ensures skills are matched to the workforce required to meet societal needs

- Creates a culture of connectedness

- Ensures connections across domains of the educational programmes such that equity is embedded throughout

- Accelerates a culture of lifelong learning

- Accepts that lifelong learning is closely linked to social accountability and the need to remain current to equitably meet societal needs

- Incubates innovation

- Understands that new technologies (medical devices, artificial intelligence, etc) require a diverse workforce that thinks differently and creatively

References

- F. H. G. Ferreira, “Not all inequalities are alike,” Nature 2022 606:7915, vol. 606, no. 7915, pp. 646–649, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-01682-3.

- “Global Vision for Education and Workforce Presented at the global conference on pharmacy and Pharmaceutical sciences education Nanjing Declaration Global Vision for a Global Pharmaceutical Workforce by Advancing Practice and Science through Transformative Education for Better Health care: ‘The FIP Vision for Education and Workforce,’” 2016.

- M. M. Islam, “Social determinants of health and related inequalities: Confusion and implications,” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 7, no. FEB, p. 11, 2019, doi: 10.3389/FPUBH.2019.00011/BIBTEX.

- “Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health - Final report of the commission on social determinants of health.” https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 [accessed Jul. 25, 2022].

- N. Ahmed, A. Marriott, N. Dabi, M. Lowthers, M. Lawson, and L. Mugehera, “Inequality Kills: The unparalleled action needed to combat unprecedented inequality in the wake of COVID-19 [summary],” 2022, doi: 10.21201/2022.8465.

- P. Braveman, S. Egerter, and D. R. Williams, “The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age,” http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218, vol. 32, pp. 381–398, Mar. 2011, doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV-PUBLHEALTH-031210-101218.

- G. Rose, K. T. Khaw, and M. Marmot, “Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine,” Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine, pp. 1–192, Sep. 2009, doi: 10.1093/ACPROF:OSO/9780192630971.001.0001.

- D. Raphael, “Social determinants of health: present status, unanswered questions, and future directions,” Int J Health Serv, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 651–677, 2006, doi: 10.2190/3MW4-1EK3-DGRQ-2CRF.

- “Equity & Equality – FIP Development Goals.” https://developmentgoals.fip.org/dg10/ [accessed Jul. 25, 2022].

- “FIP-EquityRx Collection Colophon”, Accessed: Jul. 25, 2022. [Online]. Available: www.fip.org

- “Accreditation Standards for Pharmacy Programs | Australian Pharmacy Council.” https://www.pharmacycouncil.org.au/resources/pharmacy-program-standards/ [accessed Jul. 25, 2022].

- “The Macy Foundation - Addressing the Next Patient Safety Emergency: Health Inequity.” https://macyfoundation.org/news-and-commentary/addressing-the-next-patient-safety-emergency-health-inequity [accessed Jul. 25, 2022].

- E. S. Diaz-Cruz, “If cultural sensitivity is not enough to reduce health disparities, what will pharmacy education do next?,” Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 538–540, May 2019, doi: 10.1016/J.CPTL.2019.02.003.

- E. U. McGee, S. N. Allen, L. M. Butler, C. M. McGraw-Senat, and T. A. McCants, “Holding pharmacy educators accountable in the wake of the anti-racism movement: A call to action,” Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 1261–1264, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1016/J.CPTL.2021.07.008.

- L. M. Butler, V. Arya, N. P. Nonyel, and T. S. Moore, “The Rx-HEART Framework to Address Health Equity and Racism Within Pharmacy Education,” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, vol. 85, no. 9, pp. 984–992, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.5688/AJPE8590.

- Pan American Health Organization, “Executive Summary of the Report of the Commission of the Pan American Health Organization on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas.” https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/51570/9789275121177_eng.pdf?sequence=8&isAllowed=y [accessed Jul. 25, 2022].

- S. S. Moghadam and S. Leal, “How should physicians and pharmacists collaborate to motivate health equity in underserved communities?,” AMA Journal of Ethics, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. E117–E126, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.1001/AMAJETHICS.2021.117.

- “Hispanic students make gains in graduation rates in Colorado - Axios Denver.” https://www.axios.com/local/denver/2022/06/07/hispanic-students-graduation-rate-colorado [accessed Jul. 25, 2022].

- “Covid and Race - The New York Times.” https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/09/briefing/covid-race-deaths-america.html [accessed Jul. 25, 2022].

The interviews below demonstrate the inequities impacting pharmaceutical education globally, and across the six WHO regions. The views represented are those of the interviewees based on their knowledge and expertise. While they do not represent the views of FIP, we acknowledge the importance of the emergent themes to our future workstreams.

Global perspective on inequities in higher education: An interview with Professor Emerita Anne H. Anderson, vice chair United Kingdom National Commission for UNESCO

We asked Prof. Anderson to share her views, opinions and facts based on the following questions:

- What is UNESCO’s perspective regarding the status of inequities in education globally?

- From your perspective, are there any relations/links/issues with kindergarten (K) and the 1st through the 12th grade(K12) education, and do they build on, and end up in equities in higher education?

- Why is it important to address inequities in higher education?

- Could you share any stories/real life situations (successes or challenges) on addressing inequities in education?

- What recommendations would you have for FIP addressing inequities in higher education, keeping the pharmaceutical perspective in view?

- What recommendations would you have for academic institutions and individuals willing to address inequities in their context?

Watch Prof. Anderson discussing the status of Sustainable Development Goals 4 with regard to equitable access to education globally. Her interview highlights notable concepts that influence inequities in education including pharmaceutical education. There is a need for educational recognition for refugees, sponsorship and economic support for underrepresented groups, and role modelling for students with families that have not pursued higher education.

Furthermore, FIP supports the UNESCO Paris Declaration, “A global call for investing in the futures of education” and expresses its strong commitment to investing in education for the future of humanity and the planet. The UNESCO Paris Declaration’s commitments are summarised below:

- Urgently tackle the educational crises and inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic

- Understand that equity, quality and efficiency are not competing goals in education

- Realise the importance of multilateral cooperation and multi-stakeholder engagement in advocating education

- Prioritise, protect and increase domestic finance for education

- Fulfil the 2015 Incheon World Education Forum and 2020 GEM education finance commitments

- Raise more revenues to increase education budgets through improved tax systems, innovative financing measures and public-private cooperation

- Invest in key policy priorities for recovery and accelerated progress towards SDG 4

Regional interviews

Regional interviewees shared their views, opinions and facts based on the following questions:

- What is your perspective regarding the status of inequities in pharmaceutical education in the region?

- What would you consider as the drivers and facilitators of inequities in education in your region?

- What would you consider as the barriers to addressing inequities in education from your perspective and which of these inequities issues is common in your region?

- Gender inequities

- Racial, ethnicity and religious inequities

- Resource-related inequities such as financial, infrastructural, human and technological inequities in pharmaceutical education

- Education-related inequities, including access, learning and quality in pharmaceutical education

- Could you share any stories/real life situations (successes or challenges) on addressing inequities in education?

- What recommendations would you have for FIP, academic institutions and individuals willing to address these education inequities within the region?

African region — Dr Prosper Hiag, president, African Pharmaceutical Forum, Cameroon, and Dr Arinola Joda, assistant secretary and editor-in-chief, African Pharmaceutical Forum

Watch Dr Hiag and Dr Joda highlight the inequities impacting pharmaceutical education in the African region. These are mainly resources and education-related inequities, especially variations in the number and quality of pharmacy schools, inadequate resources for training and access to education, thus leading to an inequitable pharmaceutical education experience and production of the pharmaceutical workforce. To promote an equitable pharmaceutical education, there is need for public and private partnerships to increase access to resources and harmonisation of education across the continent.

The Americas region — Dr Eduardo Savio, president of the Pharmaceutical Forum of the Americas

Watch Dr Savio highlight that, despite the efforts to promote equitable pharmaceutical education experience in the Americas, there are still variations between higher education institutions. The current inclusive perspective has presented itself as a legitimate and recurrent element in the agenda of contemporary public policies in the Americas region. For a more equitable pharmaceutical education across the region, there is need to understand the cultural background and diversity of thoughts and viewpoints, to build an assertive approach to equity in the society. It is also needed to incorporate into formal education a structured approach to equity, which is generally missing.

European region — Prof. Lilian Azzopardi, FIP Academic Institution Membership (AIM) advisory committee member, and head, Department of Pharmacy, University of Malta, Malta

Watch Prof. Azzopardi shine a light on the status of inequities across Europe, where schools of pharmacy have developed to improve greater access to education. However, there is still room for improvements in general access to higher education across the region. Providing opportunities for reflections on these inequities in education, networking and best practice sharing with a region-wide model for addressing inequities will be instrumental to promoting a more equitable pharmaceutical education experience.

Eastern Mediterranean region — Dr Nadia Al Mazrouei, president, Eastern Mediterranean Pharmaceutical Forum

Watch Dr Mazrouei highlight how the level of inequities impacting pharmaceutical education in the Eastern Mediterranean region varies across the region, and how different countries have different situations and barriers. There is room for improvements for resource- and education-related inequities due to variations across the region. Addressing these inequities through provision of effective strategies for quality and accessible education will support equitable pharmaceutical education.

South-East Asian region — Dr Rajani Shakya, FIP AIM advisory committee member, and associate professor, Department of Pharmacy, Kathmandu University, Nepal

Watch Dr Shakya emphasise that education is a basic human right that affects all aspects of life. Notably, despite the regional embracement of diversity in the South-East Asian region, there is still room for improvements in the accessibility of education to all socioeconomic groups and strata. An intentional provision of resources to improve accessibility through students’ scholarships, and identifying and supporting underrepresented students in pharmacy schools, are first steps towards improving access to a more equitable pharmaceutical education in the region.

Western Pacific region — Mr John Jackson. President Western Pacific Pharmaceutical Forum

Watch Mr Jackson discuss the discrepancies and variation in pharmacists’ education within the Western Pacific region, and how these correlates with inequities within the system, institution, society and region. Promoting academic exchanges, mentorship opportunities and trans-national research across the region, especially between countries at different development levels, will further address these discrepancies.

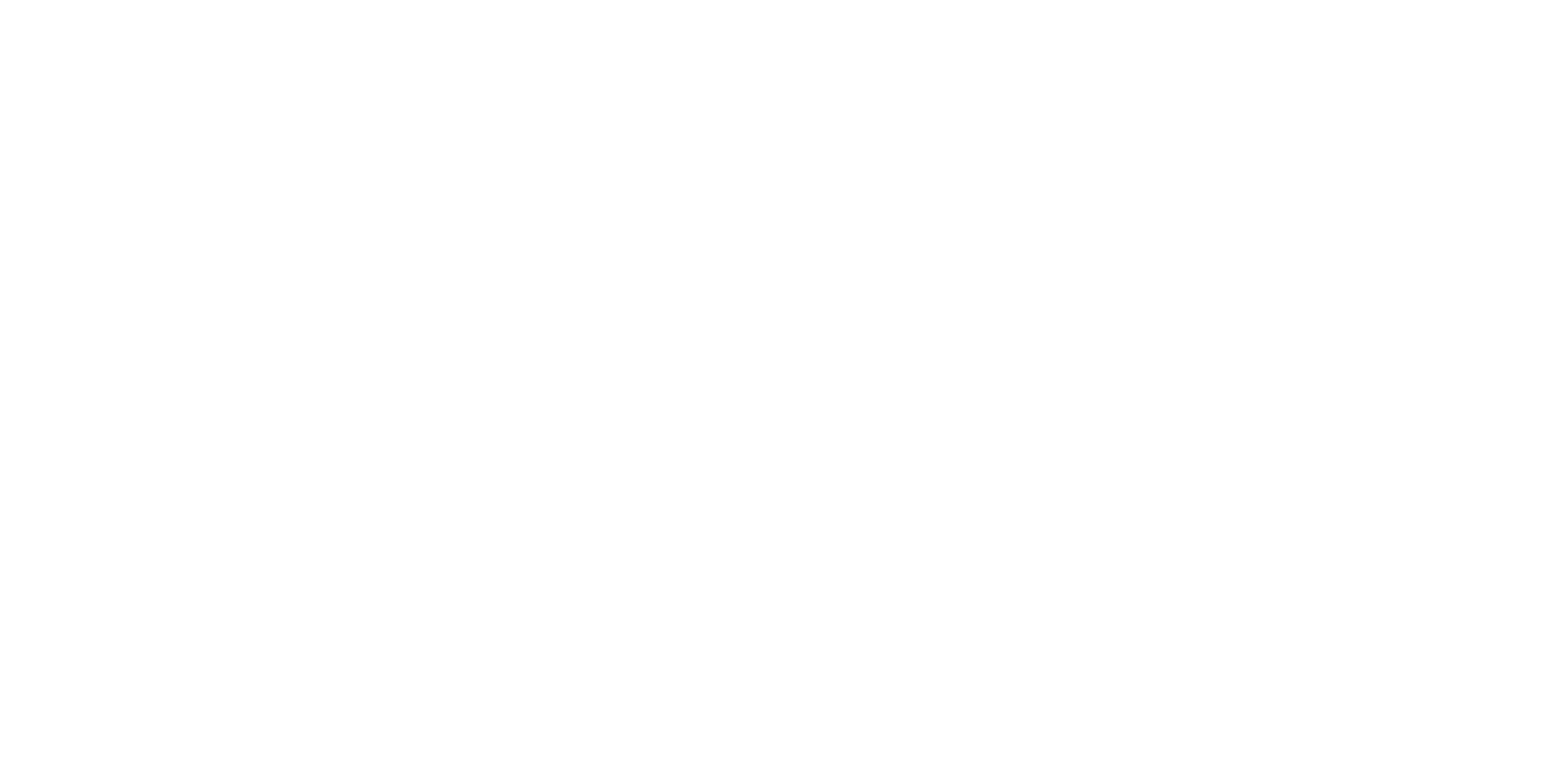

Chapter 2 examines the four inequity themes that impact on pharmaceutical education, namely:

- Theme 1 — Gender inequities

- Theme 2 — Racial, ethnicity and religious inequities

- Theme 3 — Resources-related inequities

- Theme 4 — Education-related inequities

These themes were aligned with major global guidance on inequities such as FIP Development Goals, UNESCO World Inequality Database on Education [WIDE] Indicators and disparities, and UNESCO GEM report Scoping progress in education [SCOPE] themes. Each theme has at least one case study around the world showcasing the real-life implications and approaches to addressing these inequities.

The views represented are those of the interviewees based on their knowledge and expertise. While they do not represent the views of FIP, we acknowledge the importance of the emergent themes to our future workstreams.

Gender inequities — opinion piece

by Dr Aysu Selcuk, education and primary health care policies specialist, International Pharmaceutical Federation, and Lecturer, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Ankara University, Turkey, and Prof. Claire Thompson, chair, FIPWiSE (Women in Science and Education) and chief executive officer, Agility Life Sciences, United Kingdom

| Key messages on gender inequities in pharmaceutical education | |

|

|

Gender inequities impacting pharmaceutical education are intersectional and are related to age, race, inadequate mentorship for women and inadequate opportunities for career advancements. |

|

|

The key factors for promoting positive education environments devoid of gender inequities include addressing gender pay gaps and work-life balance, creating supportive and safe working environments, providing opportunities for professional development, recognition and empowerment, and supporting women in leadership. |

Gender inequity is a worldwide issue that is increasingly being discussed in public.1 It is crucial that women and girls have equal rights and opportunities to obtain a sustainable future in society.2 Gender equity is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals suggested by the United Nations.3 Similarly, equity and equality is one of the 21 Development Goals of FIP.4 FIP added this issue to its key programme list and launched an initiative named FIP Women in Science and Education (FIPWiSE) on 11 February 2020, the United Nations International Day for Women and Girls in Science, to champion and enable women in pharmaceutical sciences and pharmaceutical education and attract female students and early career professionals into the field.5 Since this initiative began, several podcasts, video series, reports and a toolkit have been published to raise awareness about the inequities in pharmaceutical education and pharmaceutical sciences and to support women in these disciplines.5

Gender inequities exist in education careers. There are gender barriers in education as described by Jean-Marie6 with regard to gender, age, race, and lack of mentoring for women. This research has highlighted that communities perceive women in leadership positions less favourably than their male counterparts. Age-related barriers occur where early-career women leaders face scepticism about their professional abilities to lead. Communities have negative attitudes about the age of early-career women in leadership, with research showing that young women are less likely to be accepted. Mentoring can be source of support for women who aspire to be leaders in education. Lack of mentorship programmes removes this support network and can inhibit women’s confidence and career development. From a healthcare perspective, male physicians are more likely to receive mentorship and sponsorship than females.7 There are also barriers related to race, with some communities having misperceptions that white men and women do the same work better than other races.

Another barrier, described by Ballenger, is the lack of opportunities for women to enter senior leadership positions in higher education.8 This can be due to the higher education institutions being irresponsive to the necessity of expanding opportunities for women.8 Organisational, structural, cultural and personal factors are also found to be associated with barriers to leadership positions for women in higher education.9

The promising enablers for advancement of women in academia have been listed by Borlik and colleagues,7 and are set out here:

- Institutional leadership promotion of change to dismantle harassment and bias

- Training and awareness about implicit and explicit bias manifestations and interventions

- Creation of diverse, inclusive and respectful environments

- Integration of these entities into policies and procedures

- Eliminating gender pay gap

- Developing self-awareness regarding impostor syndrome

- Creating a personal career success inventory

- Documenting steps taken to earn achievements

- Celebrating accomplishments

- Maintaining a record of positive feedback

- Practising thought stopping and challenging cognitive distortions

- Seeking mentors and sponsors or mentorship and sponsorship programmes designed to address underrepresentation for women

- Paid parental leave, part-time options, flexible schedules, job-sharing, remote working options, onsite breast-feeding support, and child care programmes

To highlight the inequality issues in education, in 2021 the “FIPWiSE Toolkit for positive practice environments [PPEs] for women in science and education” was published. The toolkit highlighted five key factors for PPEs and acts as a repository of areas for progression and possible solutions that can be implemented by professionals, employers and policy makers to generate and maintain supportive working environments.10 In this article, these factors will be used to categorise direct and indirect examples of inequities in pharmaceutical education from the perspective of women in education/academia.

Factor 1. Equal incentives for equal work

According to a study conducted by Stanford University School of Medicine and University of California San Francisco, women were found to be paid less than men at the highest levels of academic medicine.11 In this study, 29 public medical schools in the USA were surveyed and the average salaries of 550 chairs of departments in 2017 were compared. Nearly one-sixth of the chairs were women, and they earned about USD 80,000 less per year than their male counterparts. Even when factors such as position title, permanent positions, cost of leaving and number of academic publications were adjusted, there is still a pay gap between men and women in academic medicine.11

Although the gender pay gap is less likely in early academic careers, between seven and 24 years of work the pay gap grows.12 This pay gap is 1.5 times bigger in academia than in industry for those with doctorate degrees in science or engineering.8 In mid-academic career, the salary of women academic scientists falls behind males by 7.2%.12 This gap has a large effect in terms of lifetime earnings of women. Therefore, it is suggested that salaries must be proactively compared and equalised across genders with every promotion and pay increase by the university leaders.12

Factor 2. Work-life balance

Balancing academic work and personal lives is one of the challenges that women in education face.13 As women still typically have more responsibilities, including domestic activities such as cooking, cleaning, aged care and childcare, they must manage more activities than men.13 These responsibilities may vary among women from different countries. For example, Asian women perform more of these domestic works than Western women13 and therefore the scale of the inequity is not the same in all countries and regions.

Although work-life balance may not be assumed as a gender issue, in academia, the pursuit of work-life balance does appear to be so.14 To cope with this, some women intentionally choose careers that are less challenging in order to balance work and personal lives.14 This causes another inequity in the number of women who work in education.

The American Association of University Professors has indicated that most women earn PhD degrees at the age of 33, with tenure occurring at around age 40, a period that coincides with childbearing and child-rearing.14 This might lead to a scenario where a woman is compelled to choose between career and family goals, something rarely required of male academics.14 Another scenario is that because of the flexible nature of higher education with regard to teaching and research obligations, work-life balance is easier or more obtainable for women.14 But this scenario is unlikely to be true. Women in academia struggle with motherhood and long working hours.14

To assist women in achieving work-life balance, a culture of balance in the workplace, which helps women to arrange and prioritise their work schedules flexibly, must be created.14

Factor 3. Creating supportive and safe working environments

Mental health in academia has suffered on account of the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced a rapid shift to remote teaching.15 But concerns about mental health in academia are not new; they did not begin only with the COVID-19 pandemic. Heavy workloads and increasing expectations around academic productivity have impacted the mental health of academics.15 The Canadian Association of University Teachers reported that precarious work is a major source of stress, and women in academia were more likely to report high level of stress.15 Stress is not an issue only for women working in academia: in earlier life in education, educational pressures and performance expectations put higher stress on girls than boys.16

Gender inequity has a significant impact on the mental health of women in academia.15 Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the long-standing inequities for women who are disproportionately affected by the brunt of additional care and housework.15 Due to these additional responsibilities, women lost their motivation and time to carry on their research15 and hence their stress levels increased. To support women on this issue, the opportunity for supportive contact with co-workers in the workplace, especially other women, can help women cope with the stressors of multiple roles. In addition, creating physical space for social support, such as informal lounges, workout facilities, cafeterias, and other gathering places, and flexibility in working hours to balance with family life, can encourage relaxation and enhance well-being.5

Factor 4. Opportunities for professional development, recognition and empowerment

Women in academia still face barriers to advancement and there is still a considerable way to go before they achieve equality with their male colleagues.17,18 This inequality may be explained by the number of women in academia, which is lower than that for men.17 According to a study conducted among UK universities, while all universities had equal opportunities policy statements, these were less likely to be practised.17,18 Universities were slow to embrace equality issues and a less effective in implementing policies compared with other institutions.18 However, the situation has been changing over the years and women now make up 33% of all academic staff in UK.17

In Turkey, although the number of women in the labour market is low, female representation in academia is relatively high compared with European countries.19 In terms of academic recognition and empowerment, among 184 universities in Turkey in 2014, only 14 (8%) have women rectors and only 9% had women are deans.19 Thus, it seems that women in Turkey may have the opportunity to find a job in academia but they are less likely to be placed in senior positions. To improve female representation in academia and senior positions in academia, mentoring and continuing educational programmes can be implemented or advanced duties and responsibilities can be given in the early stages of their careers.

Factor 5. Women in leadership

Women are often underrepresented in senior positions.5 In academia, especially for pharmacy, despite having predominantly female students, gender inequities in leadership positions remain.5 However, in Australia, the percentage of women in leadership positions in academia, including associate professors, professors and senior managers, increased from 21.0% in 2001 to 41.2% in 2021.16 In 2021, women accounted for 48.1% of all academics in Australia.20

Nowadays, more institutions are beginning to recognise the value of diversity among faculty and board members.21 They are likely to hire women and place them in senior positions.21 Women’s representation in academic leadership has been growing, but men still hold far more of the top administrative positions.10 In the context of pharmacy, while the pharmacy workforce is mainly female, women are less likely to be in leadership or decision-making positions.22

To increase the number of women in leadership in academia, women must have the same access to leadership positions as their male colleagues.5 Colleagues, senior managers and family members must support them in establishing their credibility. Employers can offer training and respecting their contributions by recognising and rewarding them.5,23

References

- Le Boedec, A., Anthony, N., Vigneau, C., Hue, B., Laine, F., Laviolle, B., Bonnaure-Mallet, M., Bacle, A., Allain, J.-S., 2021. Gender inequality among medical, pharmaceutical and dental practitioners in French hospitals: Where have we been and where are we now?. PLOS ONE 16, e0254311.. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254311.

- Bukhari, N., Manzoor, M., Rasheed, H. et al. A step towards gender equity to strengthen the pharmaceutical workforce during COVID-19. J of Pharm Policy and Pract 13, 15 [2020]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-020-00215-5.

- UN Women. SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-and-the-sdgs/sdg-5-gender-equality. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- FIP Development Goals. DG 10. Available at: https://developmentgoals.fip.org/dg10/. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- FIPWiSE. Available at: https://www.fip.org/fipwise. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Jean-Marie G. The Subtlety of Age, Gender, and Race Barriers: A Case Study of Early Career African American Female Principals. Journal of School Leadership. 2013;23[4]:615-639. doi:10.1177/105268461302300403

- Ballenger J. Women’s Access to Higher Education Leadership: Cultural and Structural. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ913023.pdf. [accessed on 30 June 2022].

- Borlik MF, Godoy SM, Wadell PM, et al. Women in academic psychiatry: Inequities, barriers, and promising solutions. Acad Psychiatry. 2021; 45: 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-020-01389-5.

- Maheshwari G, Nayak R. Women leadership in Vietnamese higher education institutions: An exploratory study on barriers and enablers for career enhancement. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 2020:1-18. doi:10.1177/1741143220945700.

- FIPWiSE toolkit for positive practice environments for women in science and education. Available at: https://www.fip.org/fipwise-ppe-toolkit. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Conger K. Women paid less than men even at highest levels of academic medicine. 2020. Available at: https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2020/02/women-paid-less-than-men-even-at-highest-levels-of-academic-medi.html. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Mullen C. Gender pay, promotion gaps wider in academia than in industry, research shows. 2021. Available at: https://www.bizjournals.com/bizwomen/news/latest-news/2021/09/gender-pay-promotion-gaps-wider-in-academia-than.html?page=all. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Welmilla I. Strategies for work-life balance for women in the academic profession of Sri Lanka. Asian Social Science. 2020;16:5.

- Mazerolle SM, Barrett JL. Work-life balance in higher education for women: Perspectives of athletic training faculty. Athletic Training Education Journal. 2018; 13 [3]: 248–258. doi: https://doi.org/10.4085/1303248.

- Bourgeult I. Mental health in academia: The challenges faculty face predate the pandemic and require systemic solutions. 2021. Available at: https://academicmatters.ca/mental-health-in-academia-the-challenges-faculty-face-predate-the-pandemic-and-require-systemic-solutions/. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Stentiford L, Koutsouris G, Allan A. Girls, mental health and academic achievement: A qualitative systematic review. Educational Review. 2021; 1-31.

- Foster N. A case study of women academics’ views on equal opportunities, career prospects and work‐family conflicts in a UK university. Career Development International. 2001;6[1]:28-38. Available at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/13620430110381016/full/html [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Bagilhole B. Academia and the peproduction of unequal opportunities for women. Science Studies. 2002. Available at: https://sciencetechnologystudies.journal.fi/article/view/55150/17985. [accessed on 27 June 2022].

- Yenilmez Mİ. Women in academia in Turkey: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Administrative Sciences. 2016; 14 [28]: 289-311.

- Calderon A. Proportion of women in academic leadership is on the rise. 2022. Available at: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=2022030210450152. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Flynn K. Academic leadership by gender. 2022. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/academic-leadership-by-gender-5101144. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- International Pharmaceutical Federation [FIP]. FIP-EquityRx Collection: Inclusion for all, equity for all. The Hague: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2019. Available at: https://www.fip.org/file/4391. [accessed on 25 June 2022].

- Frize M. Women in leadership: Value of women’s contributions in science, engineering, and technology. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Women and ICT Creating Global Transformation - CWIT ’05. ACM Press; 2005:4-es. doi:10.1145/1117417.1117421.

Country cases

Country cases give real life situations of gender-related inequities in pharmaceutical education with examples of how these inequities were addressed in the education context as well as which organisations can support addressing these inequities. The views represented are those of the interviewees based on their knowledge and expertise. While they do not represent the views of FIP, we acknowledge the importance of the emergent themes to our future workstreams.

Lebanon — country case

by Dr Dalal Hammoudi Halat, Lebanese International University, Lebanon

Could you explain why you have selected your preferred theme, gender inequities, and how it has implications on you, your colleagues and your workplace, personally or professionally?

The pharmaceutical workforce is mostly comprised of women and, in my culture, pharmacy is observed as a career which allows balancing of a proper professional life with having a family. Nevertheless, today, women’s roles often include family responsibilities, caregiving for children and/or elderly parents (statistically more likely for women), and work duties, as well as other roles. Even within their careers, women are usually expected to accept performing tasks that are less rewarding or less recognised, making them shoulder the burden of low-value or unpaid assignments, therefore missing out on the more significant tasks, promotion and personal development opportunities. As demands rise to accomplish all these various roles, women can feel overwhelmed with pressure and unmet obligations. Consequently, they may feel a sense of failure in not being able to meet expectations for themselves and for others. Women may spend more time meeting the needs of others rather than nurturing their own needs, while functioning at high stress levels. There is no doubt that COVID-19 has deepened such gender inequities, and has exposed gendered vulnerabilities disproportionately affecting women. For example, according to UN Women,1 about 29% more childcare during the pandemic was done by women compared with men, and for women in science the pandemic has witnessed a decline in their publishing capacity of peer-reviewed scientific articles. For academic women in pharmaceutical education, with an often demanding job on top of all other commitments, gender gaps still exist, especially regarding access to the higher positions.

Could you explain how the inequity theme you selected has been addressed in your country or workplace, e.g., through strategies, policies or actions?

In my institution, women in academic pharmacy are offered training, mentorship and promotion roles equal to those of men, and based only on academic profile, scientific achievements, capacities, skills, and service to academia and the profession. With an leadership attentive to gender concerns, we have never observed gender-based discrimination among pharmacy educators. Women pharmacy academics play major roles in governance, initiate and mentor research, realise internal and external collaborations, engage in training and professional development opportunities, and undertake a variety of service roles to the pharmacy profession as well as to the civil community outside academia. Remarkably, women at my institution have liaised with colleagues from other institutions and from abroad to realise joint scholarly work, and have been selected as members in highly ranked professional bodies and as leaders in high-calibre academic teams.

To keep female academics from becoming overwhelmed, stress assessment and levels of workload are routinely measured, and a culture that fosters the reduction of psychological distress is nurtured, which is applied to all academics, regardless of their gender. However, the influence on women should be substantial, given that women form most of our workforce.

Could you list organisations (global, regional or national) whose initiatives address inequities in education?

- The Order of Pharmacists of Lebanon https://www.opl.org.lb/

- The Arab Institute for Women https://aiw.lau.edu.lb/

Reference

- UN Women. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2022/06/un-women-and-undp-report-five-lessons-from-covid-19-for-centering-gender-in-crisis. [accessed on 16 August 2022].

Racial, ethnicity and religious inequities — opinion piece by Dr Khalid Garba Mohammed, Department of Pharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Technology, Bayero University Kano, Nigeria, and Pharmaceutical Engineering Group, School of Pharmacy, Queen’s University, Belfast, United Kingdom

|

Key messages on racial, ethnicity, and religious inequities in pharmaceutical education |

|

|

Acknowledgement of ethno-religious differences and inequities in pharmaceutical education is a first step to addressing these inequities. |

|

|

To close ethno-religious gaps in representation by faculty members, it is imperative to increase the number of students and graduates coming from different racial backgrounds and support their progression to postgraduate training. |

|

Incorporating cultural intelligence into pharmacy curricula through cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural practice and cultural desire will facilitate addressing these inequities. |

|

|

Diversifying, enhancing inclusion, and practising equity-minded pedagogy in pharmaceutical education are of particular importance to address inequities in healthcare globally. |

|

Pharmacy schools must provide an inclusive environment for all staff and students to enable them to achieve their potential by welcoming applicants from all backgrounds, and offering supportive work and study solely on the basis of merit and regardless of ethno-religious affiliations. |

Introduction

Formal education is neither universal nor equal nor equitable across different racial, ethnic and religious beliefs around the world.1 Many consider ethnicity as similar in concept to race. However, race has often been distinguished because of physical characteristics, especially skin colour, whereas ethnic distinctions focus on cultural differences such as language, history and customs.2.

Many studies indicate that there are differences in educational accomplishment and attainment among different ethno-religious groups. It is shown that correlations between racial, ethnicity, religion and educational attainment are partly explained by differentials such as parental endowments and social status.3,4 For instance, in the USA, during the late 1960s most African American, Latin American and indigenous American students were educated in wholly segregated schools funded at a level lower than those serving the white majority and they were excluded from many higher education institutions entirely.2

Similarly, evidence has shown that the varying distribution of religious beliefs and attitudes towards Western education across ethnic groups mostly reflects differences in educational attainment. For instance, Nigeria, one of the most populous countries in Africa, has over 250 ethnic groups and counts numerous religious denominations that can be broadly categorised as Christian or Muslim. There is a long-documented history of a gap in formal educational attainment by age among the Christian and Muslim populations and ethnic groups, which continues to persist even after the supply of educational infrastructure. There are higher rates of formal educational attainment among the ethno-religious groups in southern Nigeria compared with their counterparts in the north of the country.4

Furthermore, a study from Britain on ethno-religious background as a determinant for educational and occupational attainment shows that skin colour and religion, operate to a greater extent, as the main mechanisms that reinforce disadvantage among some groups or to facilitate social progress among others. The direction and strength of their influence appear to depend on whether the specific ethnicity or culture)is seen as compatible or outlandish in relation to the dominant culture.5

A study on a global scale indicates that about four in 10 Hindus (41%) and more than one-third of Muslims (36%) have no formal education, reflecting that education levels may vary by religion. In other religious groups, the proportions without any formal education range from 10% of Buddhists and 9% of Christians to 1% of people of Jewish faith. While recognising ethno-religious and education inequities as a global threat to equity in diversity and inclusiveness, which also undermines the United Nation’s SDG 4, we must also recognise that educational inequity varies across regions and between countries. As an example, in most low- and middle-income countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America, the educational disparity is not only between rich and poor, or between different ethno-religious groups, but is also reflected in limited enrolment of women at lower and higher levels of educational institutions.6 This unarguably deters progress on UN SDGs 4 and 5 (Gender equality).

Recognising these inequities in pharmaceutical education perspectives, first, it should be acknowledged that pharmaceutical education has undergone major paradigm changes in the past two to three decades, embracing several technological advancements in teaching and research. Ethno-religious disparities exist in pharmaceutical education as well. For instance, a recent study demonstrates that belonging to specific ethnic groups, combined with other factors such as completing primary or secondary education from a different country, had an impact on success during pharmacy training in the United Kingdom. As a result, there is a clear disparity in preregistration pharmacy trainees in 2019, when only 13% of trainees were Black.

The study identified four key root causes and factors:

- Pharmacy students belonging to minority groups can feel isolated and are less likely to benefit from peer network support. These trends are more important for mature students, who are likely to have to balance studying with family commitments and financial responsibilities.

- A perceived lack of Black-African role models within the pharmaceutical education and training pathway can impact the motivation of students of a similar background.

- Pharmacy students who have completed their primary and secondary education in other countries can struggle to adapt to teaching methods and assessment styles in the country where they receive their higher education and have less confidence to ask questions or request feedback from tutors.

- Overseas pharmacy students who have a poorer command of the English language can feel hindered during their initial education and training.

In a similar study from the United States, underrepresented racial minority pharmacy students were asked about their live experiences in a predominantly and historically white institution. Findings from this survey highlighted that pre-pharmacy school factors, such as pipeline programmes, work experiences, family and underrepresented racial minority health professionals, impacted students’ decision to attend pharmacy school. Lack of diversity, feeling unwelcomed and concerns about cultural competency and group work challenges are some of the experiences the students shared in the survey. Pharmacy students were inhibited by the mental impact of socio-political events, the pressures of representing their race/ethnicity and feeling inferior. Students took several actions to navigate the pharmacy school, including being motivated by underrepresented racial minority faculty members, finding solace and support with other underrepresented racial minorities, seeking cultural competence-related experiences to complement the curriculum, and strategically remaining silent or speaking up during group work conflicts.8

Regarding any associations with religion, among the 2018–19 preregistration trainees in the UK, 36% reported as Muslim, 26% as Christian, and 20% reported they did not have a religion.6Even though the figures did not represent all religious group of pharmacist trainees in the UK, the difference may translated in religious disparity in the pharmaceutical workforce.

Impacts on pharmaceutical workforce, public and global health

While pharmacy professionals should not impose their own ethno-religious beliefs on patients, they should not shy away from discussion where it relates to the person’s care (for example, advice on taking medicines during periods of fasting). Pharmacy professionals need to be aware of, and be sensitive to, the many different needs and perspectives of patients. They need to be aware that individual patient reactions to clinical situations can be influenced by their religion or belief, or the strength of their beliefs, and need to be sensitive to cultural, social, religious and spiritual factors, as well as clinical factors.7 Thus, less diverse ethno-religious groups of pharmacy students will give rise to a skewed pharmaceutical workforce in terms of ethno-religious inclusiveness, and that will impact the roles of pharmacists in public health from the global perspective.

Barriers to addressing ethno-religious inequalities in pharmaceutical education

The question is how can we prepare a robust future pharmaceutical workforce to serve an increasingly diverse population of patients. The special report of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s (AACP) Argus Commission, “Diversity, and inclusion in pharmaceutical education”, explored five key barriers to addressing diversity and inclusion in pharmaceutical education: consideration of diversity in society, application pipeline, current students, pharmacy faculty, and the AACP and the organisation’s member institutions. The special report established that more work must be done to ensure commitment to diversity in pharmaceutical education, which is by and large going to translate to having diversity in the pharmaceutical workforce.8

Recommendations

Having a diversity and inclusion charter for recruiting pharmacy faculty members to serve not only teaching, precepting and research purposes, but also as role models to guide and impact the motivation of pharmacy students of diverse ethno-religious backgrounds is one of the ways to address ethno-religious inequity in pharmaceutical education. Therefore, pharmacy schools must be committed to addressing the five key barriers identified by the AACP Argus Commission. Pharmacy schools must provide an inclusive environment for all staff and students to enable them to achieve their potential. This can be accomplished by welcoming applicants from all walks of life and offers of work and places to study being made solely on the basis of merit, regardless of ethno-religious affiliations.

References

- Pew Research Center. Religion and Education Around the World: Large gaps in education levels persist, but all faiths are making gains – particularly among women [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://www.pewforum.org/2016/12/13/religion-and-education-around-the-world/.

- Unequal opportunity: Race and Education, by Linda Darling-Hammond [1998].

- Sander W. The effects of ethnicity and religion on educational attainment. Econ. Educ. Rev. 1992;11:119–135.

- Dev P, Mberu BU, Pongou R. Ethnic inequality: Theory and evidence from formal education in Nigeria. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change. 2016;64:603–660.

- Khattab N. Ethno-religious background as a determinant of educational and occupational attainment in Britain. Sociology. 2009;43:304–322.

- Gutiérrez C, Tanaka R. Inequality and education decisions in developing countries. J. Econ. Inequal. 2009;7:55–81.

- Becuwe J, Reading D. Equality impact assessment Consultation on the initial education and training standards for pharmacists. 2019;10–11.

- Bush AA. A conceptual framework for exploring the experiences of underrepresented racial minorities in pharmacy school. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020;84.

Racial, ethnicity and religious inequities — opinion piece by John M. Allen PharmD, College of Pharmacy, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA, Sally A. Arif, PharmD, Midwestern University, College of Pharmacy, Rush University Medical Center, Downers Grove, Illinois, USA, Lakesha M. Butler, PharmD, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, School of Pharmacy, Edwardsville, Illinois, USA, and Midwestern University, College of Pharmacy, Downers Grove, Illinois, USA, Jacob P. Gettig, PharmD, MPH, Midwestern University, College of Pharmacy, Downers Grove, Illinois, USA, Miriam C. Purnell, PharmD, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, School of Pharmacy and Health Professions, Princess Anne, Maryland, USA, Ettie Rosenberg, PharmD, West Coast University, School of Pharmacy, Los Angeles, California, USA, Hoai-An Truong, PharmD, MPH, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, School of Pharmacy and Health Professions, Princess Anne, Maryland, USA, Latasha Wade, PharmD,

Division of Academic Affairs, Elizabeth City State University, Elizabeth City, North Carolina, USA, and Oliver Grundmann, PhD, MS, College of Pharmacy, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

Inequities in education for people of colour and those from other underrepresented backgrounds begin in early education and persist through graduate and professional school. People of colour located in disinvested and under-resourced communities in the USA and other countries are less likely to receive grade-appropriate coursework and more likely to be taught by inexperienced teachers.1 In addition, school districts serving primarily people of colour are receiving lower quality or fewer resources compared with a majority white district.2 Religious inequities, for example, are reflected in a report addressing higher stress, harassment and mental challenges faced by Muslim students if they are the minority in their school district.3 Inequities in education through high school lead to a discrepant lower enrollment of underrepresented students in secondary education, lower graduation rates for both undergraduate and graduate degrees, and especially a lower rate of graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) degrees.4 Factors which impact women and underrepresented populations entering and completing graduate studies include financial support, supportive relationships with peers, postdoctoral candidates, graduate advisors, and faculty members who belong to an underrepresented group.5

Diversifying, enhancing inclusion and practising equity-minded pedagogy in pharmaceutical education is of particular importance to address inequities in health care globally. Both conscious and unconscious biases of healthcare professionals towards racial and religious minorities negatively impact treatment outcomes and increase the economic burden of disease globally.6–8 In the USA, recruitment of underrepresented candidates to the pharmacy profession, and their retention, has consistently faced major barriers, including meeting high tuition costs, satisfying academic prerequisites, and a lack of support before and during the application process.9,10

Lower entry numbers of underrepresented students into healthcare professions have also been shown in the Netherlands, where higher chances of enrolment in academic institutions are associated with factors such as higher income, having a parent who is a practising healthcare professional and being a female candidate, whereas those with a migration background had fewer chances.11 Since the end of apartheid in South Africa, substantial changes to pharmacy education have been undertaken by merging two pharmacy programmes that previously served a primarily Black (Medical University of South Africa) and White (Technikon Pretoria) student population.12 In conjunction with that, another initiative extended pharmacy ownership to include non-pharmacists in the hope of increasing pharmacy access in rural areas. Both initiatives, however, have not resulted in diversification of, or increased pharmacy services in rural South Africa.13

While representation of people of colour and women in the pharmacy workforce is important to provide culturally responsive health care to a diverse population,14 a contributing factor to recruiting and retaining underrepresented students is the diversity of the faculty and faculty representation of those groups. The relative increase of women faculty members at US colleges and schools of pharmacy is not mirrored by an equal increase in faculty members of colour, which reflects the increase in women graduates from institutions as opposed to their having been little change for people of colour.15 To close the gap in representation by people of colour in faculties, it is imperative to increase the number of students and graduates of colour and their progression to postgraduate training.16 One model by which to increase the enrolment of people of colour in pharmacy schools and continue their academic career to graduate studies is a collaboration between a historically Black college and university (HBCU), in the given case Xavier University of Louisiana, with an institution that offers graduate pharmaceutical education, in this case Ohio State University.17 Providing a path for undergraduate people of colour to enter the profession of pharmacy can enable a more diversified workforce and similarly diverse academic faculties to facilitate inclusion and equity for patients and students alike.

While diversity initiatives and policies should be championed by the leadership of institutions of higher education, it is also the responsibility of faculties at a departmental level to embrace the diversity of colleagues.18 On the departmental level, the following strategies can serve to enhance diversity:

- Integrate diversity, equity, inclusion in the mission and vision of the department;

- Help define and demonstrate how each department faculty member fits into the overall mission and vision of the department. This philosophy should also guide new hires and the faculty search process;

- Practice inclusion and building collegiality among faculty members;

- Facilitate effective mentoring relationships between faculty members;

- Encourage and facilitate cross-discipline or cross-field collaborations between faculty members;

- Utilise the diverse knowledge and skills of faculty members to help identify resource allocation needs and priority areas within the department;

- Implement best practices for religious accommodations to attract and retain diverse faculty members, students and staff; and

- Review, identify and correct disparities and bias in salary/resource distribution, performance evaluation, and promotion and tenure opportunities.

Like the field of medicine,19 pharmacy education is currently developing a framework for a holistic approach to incorporating diversity, equity and inclusion into the academic curriculum, although it is not yet well established. One such approach is to incorporate cultural intelligence into the pharmacy curriculum .20 This framework encompasses four domains for lifelong learning:

- Cultural awareness;

- Cultural knowledge;

- Cultural practice; and

- Cultural desire.

Based on these four domains, objectives were developed according to Bloom’s taxonomy to incorporate learning outcomes for students.20 An initial application of the framework indicated increased cultural intelligence although any potential for long-term impact depends on its adoption into pharmacy school curricula. Ultimately, pharmacy education must move beyond a goal of cultural intelligence and competence. The academy must encourage cultural humility, which is defined as “a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and critique, to redressing power imbalances . . . and to developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations”.21

As established by the WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce in 2008, 22 pharmacy workforce priorities aim to provide an appropriately trained pharmacy workforce and a competent and committed academic workforce to train enough new pharmacists. Both priorities are related to and should include diversity, inclusion, equity efforts to ensure pharmacists optimise healthcare outcomes for patients and serve the community as interdisciplinary healthcare professionals. Colleges and schools of pharmacy should consider incorporating diversity, inclusion, equity as part of their mission and values to advance national and international pharmacy services.

References

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L. Inequality in Teaching and Schooling: How Opportunity Is Rationed to Students of Color in America - The Right Thing to Do, The Smart Thing to Do. National Academies Press; 2001. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223640/

- US Department of Education. Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) for the 2013-14 School Year.; 2016. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-2013-14.html

- Oberoi AK, Trickett EJ. Religion in the Hallways: Academic Performance and Psychological Distress among Immigrant origin Muslim Adolescents in High Schools. Published online 2018. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12238

- Allen-Ramdial SAA, Campbell AG. Reimagining the Pipeline: Advancing STEM Diversity, Persistence, and Success. Bioscience. 2014;64(7):612-618. doi:10.1093/BIOSCI/BIU076

- Stockard J, Rohlfing CM, Richmond GL. Equity for women and underrepresented minorities in STEM: Graduate experiences and career plans in chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(4). doi:10.1073/PNAS.2020508118/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL

- Alzahrani F. Understanding the Relationship Between Pharmacists’ Implicit and Explicit Bias and Perceptions of Pharmacist Services Among Arab and Black Individuals. Published online 2019.

- Ding A, Dixon SW, Ferries EA, Shrank WH. The role of integrated medical and prescription drug plans in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in medication adherence. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 2022;28(3):379-386.

- Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:219-229. doi:10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2017.05.009

- Hayes B. Increasing the representation of underrepresented minority groups in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1). doi:10.5688/AJ720114

- Alonzo N, Bains A, Rhee G, et al. Trends in and Barriers to Enrolment of Underrepresented Minority Students in a Pharmacy School. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(7):1547-1557. doi:10.5688/AJPE6925

- Mulder L, Wouters A, Twisk JWR, et al. Selection for health professions education leads to increased inequality of opportunity and decreased student diversity in The Netherlands, but lottery is no solution: A retrospective multi-cohort study. Med Teach. 2022;44(7). doi:10.1080/0142159X.2022.2041189

- Summers R, Haavik C, Summers B, Moola F, Lowes M, Enslin G. Pharmaceutical education in the South African multicultural society. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2001;65(2):150-154.

- Moodley R, Suleman F. To evaluate the impact of opening ownership of pharmacies in South Africa. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2020;13(1). doi:10.1186/S40545-020-00232-4

- Hayes B. Increasing the representation of underrepresented minority groups in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1). doi:10.5688/AJ720114

- Chisholm-Burns MA, Spivey CA, Billheimer D, et al. Multi-institutional study of women and underrepresented minority faculty members in academic pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(1). doi:10.5688/AJPE7617

- Campbell HE, Hagan AM, Gaither CA. Addressing the Need for Ethnic and Racial Diversity in the Pipeline for Pharmacy Faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):950-958. doi:10.5688/AJPE8586

- Bleidt B. Cooperative Approaches to Stimulating Minority Participation in Graduate Pharmaceutical Education. In: Multicultural Pharmaceutical Education. Routledge; 2013:55-74.

- Chisholm-Burns MA. Diversifying the team. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):44. doi:10.5688/AJ720244

- Nivet MA, Castillo-Page L, Schoolcraft Conrad S. A Diversity and Inclusion Framework for Medical Education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):1031. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001120

- Minshew LM, Lee D, White CY, McClurg M, McLaughlin JE. Development of a Cultural Intelligence Framework in Pharmacy Education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):934-948. doi:10.5688/AJPE8580

- Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117-125. doi:10.1353/HPU.2010.0233

- Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, et al. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce: enabling concerted and collective global action. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6). doi:10.5688/AJ7206127

Resource-related inequities — opinion piece by Zelna Booth, Rubina Shaikh, Neelaveni Padayachee and Yahya E. Choonara, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, Johannesburg, South Africa.

|

Key messages on resource-related inequities in pharmaceutical education |

|

|

Resource-related inequities in pharmaceutical education arise from financial, human capital, technological and infrastructural issues. |

|

Low- and middle-income countries are affected most, due to inadequate resources to train students to the highest standards of education |

|

|

Engagement of governments and private stakeholders as well as increased research outputs will go a long way towards improving equitable access to resources for pharmaceutical education |

Introduction

A key tenet of many countries to accelerate economic growth is to have a highly qualified and trained workforce. For the pharmaceutical workforce to actively function within the profession and drive such economic growth, pharmaceutical educational programmes and facilities responsible for nurturing and equipping future pharmacists need to be quality assured against the necessary standards, irrespective of the inequities that may be faced by such educational institutions. The inequities in pharmaceutical educational resources that are necessary to produce well-trained and high-quality graduates can be categorised into four main themes: infrastructure, finance, human capital and technology. To support the delivery of high-quality pharmaceutical education, equitable access to these resources is essential in any educational setting. Despite the awareness and importance of having these resources available and accessible to all, inequity among regions of the world still exists. Such inequities disproportionately affect low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) in delivering pharmaceutical education. 1–4

In poorly resourced LMICs, academic pharmacists are required to be more adaptable to maximise the limited resources available to ensure quality standards are met. Hence, curriculum innovations are a must, and many forward-thinking institutions still produce exceptional graduates.5 Furthermore, resource inequities can be labelled as country-, institution- or student-specific, thus negating a “one size fits all” solution to addressing the inequities.6

Infrastructural, spatial and industry access inequities

The student experience for pharmaceutical education differs between institutions in terms of accessing teaching and learning facilities such as libraries, laboratories and lecture venues. There are global and regional disparities in the type and quality of pharmacy educational infrastructure that is made available to students. The need to train more pharmacists to meet the healthcare needs of LMICs has pressurised universities to upwardly adjust their enrolment plans on pharmacy programmes. This places further strain on the size of teaching and practical training facilities, in addition to insufficient equipment and learning resources.7

Furthermore, many institutions in LMICs struggle with poor infrastructure and equipment as well as the lack of conducive environments for teaching and research (e.g., poor wifi connectivity, insufficient electricity supplies or the absence of suitably qualified academic pharmacists), which severely affects the pharmacy training capabilities of such institutions. In addition, a limited access to patients for student-patient interaction during workplace-based learning negatively impacts the quality of communication and patient counselling skills needed to provide pharmaceutical care as opposed to institutions in other regions and countries where this capability exists.8

The sole focus for many pharmacy schools is on preparing pharmacy graduates as patient-oriented medicine experts, thus producing graduates who are lacking key skills, including interprofessional teamwork, leadership attributes, critical thinking and analytic skills, necessary for the evolving role of the pharmacist. In promoting these skills and qualities, there is a need to engage with relevant collaborators and stakeholders as resources, and involvement from stakeholders in the development and assessment of the school’s activities is necessary to ensure relevance, quality and effectiveness of the curriculum. Opportunities for how to better equip pharmacy students requires reimagination of work-based experiences and involvement of the pharmaceutical industry and other stakeholders. While many institutions have access to these resources and stakeholders, many others have limited access due geographical and financial limitations.9, 10

Financial inequities