Nilhan Uzman, FIP Lead for Education Policy and Implementation and Lead for FIPWiSE Programme, The Netherlands

Dr. Aysu Selcuk, FIP Educational Partnerships Coordinator and FIPWiSE Toolkit Project Coordinator; Lecturer, Ankara University, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Turkey

Prof. Claire Thompson, Chair, FIPWiSE and CEO, Agility Life Sciences, United Kingdom

Dr. Catherine Duggan, CEO, FIP, The Netherlands

By Dr Catherine Duggan, FIP CEO, The Netherlands

In our working lives, the places we work are as important as the people we work with and the job itself. When an environment is supportive, enabling and collaborative, we can all thrive. When an environment is neither all or is none of these things, we can deteriorate and our productivity, along with our well-being can suffer. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when so many of us were unable to enter our usual work environments, adapting our online communities and ways of working was essential to ensure we thrived.

Once of the biggest benefits of being a CEO in a federation such as FIP is the ability to collaborate and grow alliances, friendships and mutual work for the benefit of all. I draw upon three such alliances. The first is FIP being a member of WHPA — the World Health Professions Alliance. The WHPA brings together the global organisations representing the world’s dentists, nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists and physicians and speaks for more than 41 million healthcare professionals in more than 130 countries. The WHPA works to improve global health and the quality of patient care, and facilitates collaboration among the health professions and major stakeholders.

Since becoming FIP CEO in 2018, I have benefited hugely from working with CEOs from four other health professions and, upon reflection, even more so during the pandemic. Many of the initiatives we have been focusing on since I joined FIP suddenly came into their own and their relevance was heightened because of the pandemic. One such programme of work was the Positive Practice Environment (PPE) work. Of course, “PPE” took on a very different importance as shorthand for “personal protective equipment”, a vital mainstay of all health professions, but the PPE programme became equally relevant and essential as the months progressed. Some very practical and feasible lessons were initiated for us all, from understanding the strengths and weaknesses of the workplace, its organisational climate and working conditions to celebrating success — from supporting effective strategies that promote resilient and sustainable health systems to joining with others, raising awareness and building alliances to make a change and to make a difference.

In an interview in this toolkit, Howard Catton, 2021 WHPA chair and CEO of the International Council of Nurses, Switzerland, recommends leveraging existing relationships with international organisations to raise the visibility and profile of the need for positive practice environments and this seems so timely as we consider the implications for the WHPA’s PPE campaign across FIP.

The second alliance, friendship and mutual work for the benefit of all I draw upon is that which we have forged with Women in Global Health (WGH). In an interview in this toolkit, Dr Roopa Dhatt, WGH executive director from the United States of America, emphasises that we do not need to “fix women” to fit into systems and policies modelled on men; instead we need to fix discriminatory systems and cultures that put obstacles in the career paths of women. FIP has been a member of the World Health Organization-WGH Global Health Workforce Network Gender Hub, since 2018, and together we are striving to fix systems that do not serve women through addressing gender equity and diversity inequalities in pharmaceutical practice, science and workforce. Enabling positive practice environments for women in science and education is our attempt to do so.

The third alliance I draw upon is FIP-WiSE (Women in Science and Education). FIP-WiSE is an initiative that has grown from a need to support and enable women across all stages of their career across all areas and sectors of science and education. This group emerged from the Pharmaceutical Workforce Development Goal (PWDG) 10 (Gender diversity and balances) which highlighted the disparity across science and education in terms of women in leadership roles, visible to us all. As the work on the FIP Development Goals (DGs) built on and extended the PWDGs, goal 10 too expanded to reflect equity and equality issues across all demographics — age, ethnicity, income levels, disease states and gender to name a few. The place of FIP-WiSE became more secure and focused FIP minds on creating useful, practical and essential spaces, places and resources for all women in science and education with the fundamental aim that these are not limited to women, but available to all. It seemed essential to consider how the work of the WHPA could be supportive of the emerging findings that environments across science and education were not always positive, nurturing, supportive and enabling; neither were there the tools to hand to support women in said workplaces to find a way through. So, the WHPA’s PPE campaign was adapted to the needs of the FIP-WISE community.

Through the alliance forged by our five professions, the supportive campaign on PPE for all across all workplaces seemed ideally placed to support our initiatives for women in science and education and, ultimately, to benefit all across the pharmacy profession. Sometimes the useful tools we develop in one area can support another area where the need becomes apparent, and a further alliance is created. As fundamental as the 17United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are to us all, we know that creating the environment for sustainable development is key if we are to flourish, even more so following a pandemic. And following a pandemic, as we take time to find our place in the world and work, we will need tools and toolkits that can enable, support and empower us, especially when the environment is less supportive and less positive than we would like.

Creating new alliances through existing alliances during a time of such crisis feels very important and the foreword of such a collaborative toolkit such as this is a very good place to acknowledge the strengths of alliances, the power of collaborations and the benefit of support FIP is proud to facilitate. Congratulations on this toolkit which I know will prove of value to all who use it and take it forward in their practice, wherever that may be.

By Prof Claire Thompson, Chair, FIPWiSE and CEO, Agility Life Sciences, United Kingdom

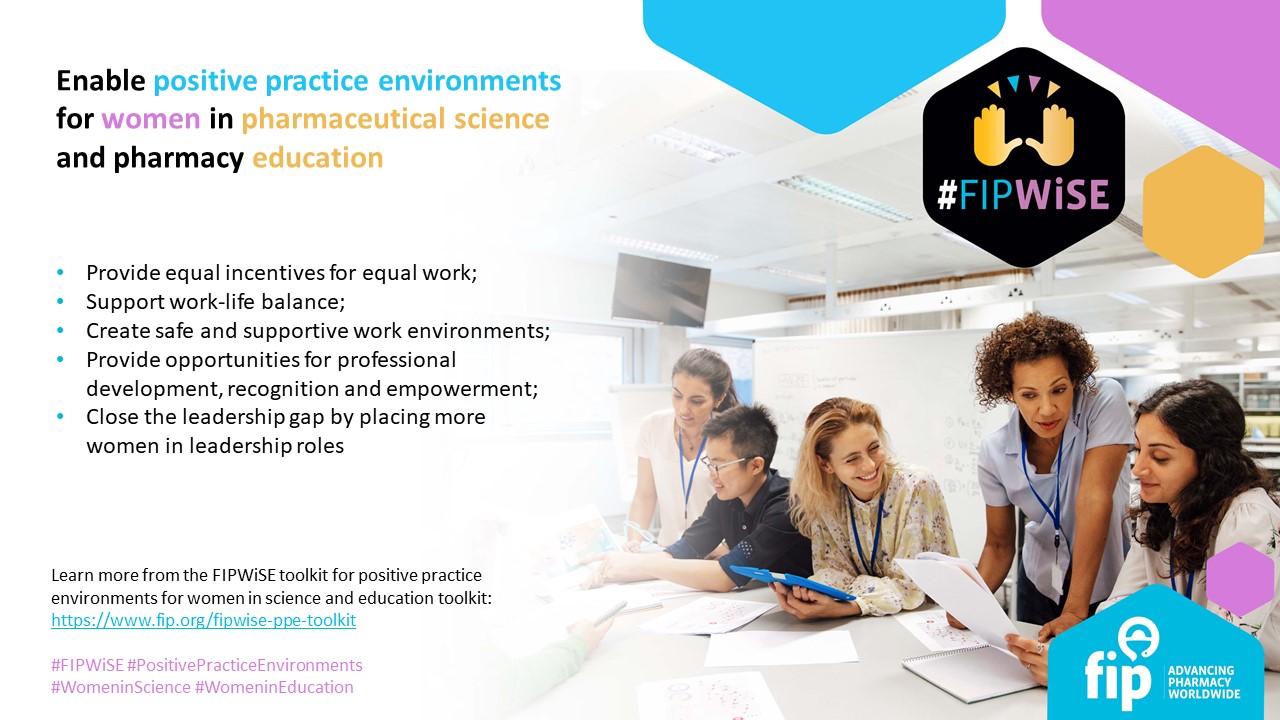

FIP is leading activities, in collaboration with World Health Professions Alliance (WHPA), to create safe, supportive and successful practice environments for the entire pharmaceutical workforce. Building on WHPA’s Positive Practice Environments (PPE) campaign, FIPWiSE (FIP women in science and education) is just one of the initiatives that FIP is utilising to create an environment where women in the pharmaceutical sciences and pharmacy education can thrive.

The FIPWiSE Enabling Workplaces Working Group and contributors from all around the world have compiled this toolkit to highlight the need for, and raise the awareness of, PPEs for women in science and education. This toolkit creates a repository of areas for progression and possible solutions which can be implemented by professionals, employers and policy makers to generate and maintain supportive working environments. The toolkit focuses on education and science workplaces, but has the opportunity to expand learnings across the entire pharmaceutical workforce.

Chapter 1 of the toolkit is about drawing attention to, and understanding the issue of PPEs in education and science. While focusing on the need to create PPEs in education and science, this chapter highlights the workplace inequities and inequalities faced by women, and how these have been amplified through the pandemic.

Chapter 2 delves deeper into five key factors which underpin PPEs, namely:

- Factor 1 — Equal incentives for equal work;

- Factor 2 — Work-life balance;

- Factor 3 — Creating supportive and safe working environments;

- Factor 4 — Opportunities for professional development, recognition and empowerment; and

- Factor 5 —Women in leadership.

These factors were identified based on WHPA’s PPE campaign, literature and shared experiences by WiSE to cover all aspects that women face in their working environments. Each factor has at least one case study from WiSE around the world. In each case, we hear real-life experiences and insight into the importance of these factors in recruiting, rewarding and retaining women in the workforce.

Chapter 3 concludes on establishing PPE in the workplace for WiSE. Here, we propose specific areas for progression and possible solutions for employers or managers (e.g., academic and research institutions and others), professionals in science and education as well as policy makers (e.g., national professional organisations) which can be put in place to create sustainable and supportive working environments for all.

Finally, Chapter 4 supports employees, individuals and policy makers to activate the PPE campaign through various media materials, such as campaign posters and social media cards for each factor. These materials are provided for readers to demonstrate their support for PPEs for WiSE (and for all). We have also included a table of similar initiatives from around the world to provide supportive resources for individuals, employers and organisations.

Women represent half the population, and more than half of the pharmacy and pharmaceutical science workforce. I am a very strong advocate that women should not be confined by their gender. Whether it is educating the future workforce, or developing new medicines or health technologies, we should ensure that women have equal voice and value at every level. By creating and maintaining PPEs we can help women to achieve their fullest potential.

Success is not a solo sport. I would like to thank all of the contributors to the toolkit, the case study authors for sharing their stories and experiences, and the FIPWiSE working groups and steering committee for their input, insight and inspiration. I hope that this toolkit can engage, enable and empower women to achieve their aspirations, and help to create an environment where the entire workforce can succeed

Interview with World Health Professions Alliance

In this interview, Howard Catton, 2021 WHPA chair, and CEO, International Council of Nurses, Switzerland, describes the WHPA’s view on the Positive Practice Environments (PPE) campaign and how it links with the pharmaceutical workforce, and women in pharmaceutical science and pharmacy education.

What’s the perspective of the WHPA regarding the current status of PPEs for healthcare professionals?

Positive practice environments, which we define as healthcare settings that support excellence and decent work conditions, have the power to attract and retain staff, provide quality patient care and strengthen the health sector as a whole. However, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to put a strain on health professionals and other healthcare workers. This pandemic has brought to the fore the very real need to recognise and support health professionals and to ensure an effective workforce. Now, more than ever, the world needs to stand up and advocate PPEs for their health professionals.

The delivery of high-quality health services depends on the competence of health workers and a work environment that supports performance excellence. The ongoing under-investment in the health sector has resulted in a deterioration of working conditions worldwide. This has had a serious negative impact on the recruitment and retention of health personnel, the productivity and performance of health facilities, and ultimately on patient outcomes. PPEs must be established throughout the health sector if national and international health goals are to be met.

In the WHPA’s view, why is it important to provide PPEs?

Health professionals are key to sustainable health systems, both now and for the future. However, the poor quality of most healthcare work environments is undermining health service delivery and driving health professionals away from their caregiving role and countries.

Unsafe working conditions are a feature of many health systems around the world. Unrealistic workloads, poorly equipped facilities, compromised personal safety and unfair compensation feature among the many factors affecting the work, life and practice of today’s health professionals. Such environments weaken an employer’s ability to offer enabling workplaces, and make it more difficult to attract, motivate and retain staff. These factors, when appropriately resourced, go a long way in ensuring an effective health professional workforce and, ultimately, the overall quality of health care delivery.

There are key elements in the workplace that have a direct positive impact on people’s health outcomes and organisational cost-effectiveness. Moreover, healthcare settings driven by people-centred care are considered to be more effective, to cost-less, and to improve health literacy and patient engagement.

What does success look like for providing PPEs for healthcare professionals?

We believe that PPEs benefit everyone — patients, health professionals, employers and managers, and health care systems. The successful implementation of PPEs would be evident where professionals are recognised and empowered, enabled and encouraged to stay in their jobs, profession and country, where employees are safe so they remain healthy, motivated and productive and where they are provided with opportunities to learn, develop, progress and save lives.

Could you tell us about the progress of the WHPA's PPE campaign in encouraging and enabling PPEs?

The focus of the first year of our campaign has been on raising awareness of what a PPE is. Through social media and a series of public webinars we have capitalised on the attention that the pandemic has put on health systems and health professionals to strongly advocate recognition, good work conditions and support for our workforce. Our multilingual factsheets and posters have been distributed by WHPA members, the FDI World Dental Federation, the International Council of Nurses, World Physiotherapy and the World Medical Association, as well as FIP.

The coming year will see continued focus on the mental health of health professionals as well as violence against health professionals. We will start to collect best practice examples from around the world as a means of highlighting what PPEs can look like and inspiring practical moves towards turning health facilities and workplaces into more positive environments.

What recommendations would you have for individuals, employers and organisations on providing PPEs to healthcare professionals?

First, take a look at your healthcare work environment and understand the strengths and weaknesses of the workplace, its organisational climate and working conditions. Secondly, make the case — with managers, other health professionals and patients — for healthy, supportive work environments, through evidence of their positive impact on staff recruitment/retention, patient outcomes and health sector performance. Present it, publish it and talk about it. Thirdly, apply the principles of positive practice environments across your health facility and national health sector, establishing and promoting positive models and introducing supportive policies.

Finally, celebrate success, in support of effective strategies that promote resilient and sustainable health systems. Join with others, raise awareness and build alliances to make a change and to make a difference. Provide more evidence on positive practice environments. Consider a catalogue of good practices in human resources management, occupational health and safety, professional development, etc.

What recommendations would you have for FIP on supporting the provision of PPEs to women in pharmaceutical sciences and pharmacy education?

- Encourage member organisations to collect and share positive examples to reinforce the case for PPEs on a global platform.

- Respond strongly and publicly to reports of workplace conditions that are not in line with PPE recommendations.

- Make the most of opportunities to chair sessions, and give keynote speeches and presentations on PPEs.

- Leverage existing relationships with international organisations to raise the visibility and profile of the need for PPEs.

Interview with Women in Global Health

In this interview, Dr Roopa Dhatt, executive director, Women in Global Health, USA, describes WGH’s view on providing positive practices to women in global health and learnings from WGH’s experience that could be applies to women in pharmaceutical science and pharmacy education, and across the entire pharmaceutical workforce.

What’s the perspective of WGH regarding the current status of PPEs for women in global health?

Women have made an extraordinary contribution to global health in all sectors, as evidenced from the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, from science and vaccine development to health policy-making and health service delivery as 70% of health and care workers. Women, as a majority among pharmacists, have been on the frontline of the pandemic, including playing a vital role in reinforcing public health measures, delivering testing and, in some contexts, vaccines. In some countries, pharmacists have also played a life-saving role in enabling survivors of intimate partner violence to get away from their abusers. Schemes where women can alert pharmacists that they need help by use of a code word have been critical as gender-based violence has risen everywhere with lockdowns in the pandemic. The contribution and expertise of women, however, has not been equally presented in leadership or in the media. Women are not only overlooked but, frequently, men are chosen to speak on subjects where women are experts.

Although women comprise the majority of the health and care workforce, they are clustered into lower status and lower paid sectors and roles. Women hold only 25% of leadership roles in health and despite women being experts in health systems, this has also been true in the pandemic. Women have not had an equal say in pandemic decision-making at global or national levels. Typically, national COVID-19 decision-making groups have had a small minority of women members. One study1 found 85% of 115 national COVID-19 task forces had majority male membership. Including equal numbers of women in leadership (with women health and care professionals, as well as people from diverse social groups and geographies) encourages more informed decisions on all policy measures, including policies on lockdowns and maintenance of essential maternity services that impact particularly on women.

So overall we see women making an extraordinary contribution to global health, made very clear by the pandemic, but not yet being rewarded equally with men in pay, in leadership, in career progression or in safe and decent work.

In WGH’s view, why is it important to provide PPEs for women in global health?

Despite applause for health workers during the pandemic, the approach to the health and care workforce has often been gender-blind, ignoring the fact that women comprise 70% of the global health workforce and face different barriers to men at work that need to be resolved. For example, the vaccine roll-out, once vaccines are finally available on an equitable basis, will require a huge surge in health workers to administer them, mainly female vaccinators. Currently, millions of women work in health systems roles, including vaccinators, either unpaid or grossly underpaid via a stipend. It remains to be seen whether mass vaccination campaigns to reach the majority of adults in a country can be effective when based on the unpaid work of women who already have a heavy load of care work.

The majority of women health workers are in lower status, low paid roles and sectors, often in insecure conditions and facing harassment on a regular basis. The pandemic started with a global shortage of 40 million health workers and an additional 18 million are needed in low-and middle-income countries to achieve universal health coverage (UHC). The pandemic has turned a global health worker shortage into an emergency — health workers have been lost to the virus and to “long COVID” and there is widespread exhaustion and mental trauma among them, especially women, who have shouldered the majority of patient care and increased unpaid care work at home. There are widespread reports from many countries that women plan to leave the health sector in large numbers because they are demoralised and tired. Low-income countries are rightly concerned that health worker shortages in high income countries will worsen and low-income countries will lose scarce health workers to better resourced countries.

PPEs are critical for women, therefore, to support them with gender transformative policies and reduce attrition from health professions. Without health workers there are no health systems. In February 2021, WGH launched the Gender Equal Health and Care Workforce Initiative with France and the WHO to advocate the urgent investment in safe, decent and equal work for women health workers central to strong health systems and global health security. We are delighted that FIP has joined us in the initiative as a supporter and commitment maker.

Have you observed any differences in practice environments between regions/countries? If yes, could you elaborate more?

There are wide differences in practice environments for women in global health between countries and regions. Countries are culturally, politically and economically diverse, and vary widely on the resourcing levels of health systems and on the approach to health systems. WGH has a fast expanding network of 25 national chapters, the majority in low-and middle-income countries, which keeps us grounded in the realities of very diverse practice environments for women in the sector. WGH is a strong advocate of UHC, having joined with 160 NGOs in 2019 to form the Alliance for Gender Equality and UHC, which we convene with Women Deliver, Sama India and SPECTRA Rwanda. We believe that gender-responsive UHC is the most effective way of addressing the health needs and priorities of all genders and reaching the most marginalised women and girls. Two years ago a political declaration from the first UN High Level Meeting (HLM) on UHC made strong commitments on gender equality. Since that time, however, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused 4.5 million deaths globally, has devastated economies and livelihoods and is far from over. We will dedicate the next two years in the lead up to the second HLM on UHC campaigning as part of the alliance for governments to fulfil the commitments made on UHC and continue delivery by the 2030 deadline. The pandemic has been a massive health, economic and social shock but this is not the time to back pedal on health or reducing inequality. There are currently very different practice environments between and within countries, but gender-responsive UHC will be the foundation for stronger health systems to combat future health shocks and for global health security.

What does success look like in providing PPEs for women in global health?

According to the FIPWiSE toolkit, women in leadership is one of the key factors that can enable PPEs. Equal representation of women in leadership needs no justification in a workforce with a majority of women. Beyond gender parity, however, leaders of all genders must promote gender-transformative policies to realise better global health. Addressing gender inequality in the health and social care sector is not solely the responsibility of women leaders.

Gender-transformative policies are defined in the WHO’s landmark 2019 report “Global health: Delivered by women, led by men” as those that “seek to transform gender relations to promote equality”. Gender-transformative leadership will be grounded in principles including:

- A framework for gender equality, women’s rights and human rights;

- Challenging privilege and power imbalances based on gender that undermine health;

- Intersectionality, addressing social and personal characteristics that intersect with gender – race, ethnicity, geography etc – to create multiple disadvantages; and

- Being applicable to leaders of any gender, not exclusively women leaders.

Gender-transformative leadership in global health and social care will aim to leave no one behind in access to health and, equally, aim to leave no one behind in leadership and decision-making.

What are the lessons learnt from your activities?

- Gender leadership gaps are driven by stereotypes, discrimination, power imbalance and privilege.

- Women’s disadvantage intersects with and is multiplied by other identities, such as race and class.

- We do not need to “fix women” to fit into systems and policies modelled on men; instead we need to fix discriminatory systems and cultures that put obstacles in the career paths of women.

- Global health is weakened by excluding female talent, ideas and knowledge.

- WGH can be a platform for enabling the women most underrepresented in global health, women from low- and middle-income countries, to enrich global health dialogue and policy with their diverse perspectives and experience.

- Women leaders often expand the health agenda, strengthening health for all.

- Gendered leadership gaps in health are a barrier to reaching the SDGs and UHC.

- WGH is most effective when working in partnership and sharing resources and best practice with like-minded organisations such as FIP.

What recommendations would you have for individuals, employers and organisations on providing PPEs to women in global health?

On leadership:

- Achieve gender parity, set targets and quotas for leadership to ensure that women, especially those from diverse backgrounds, are accessing decision-making roles;

- Encourage gender transformative leadership as a responsibility for leaders of all genders; and

- Support women’s networks and movements.

On underpaid or unpaid work:

- Support gender gap legislation and publish your gender pay gap; and

- End the practice of engaging women unpaid in health systems roles, ensuring that all women workers have equally paid, formal sector work.

On closing the data gap:

- A critical first step is to collect sex disaggregated data; and

- A second critical step is to take an intersectional approach to policy and data collection, analysing the social identities, such as race, ethnicity, gender identity, disability, class, caste etc that can intersect with gender and multiply disadvantage for particular social groups. (This is particularly important in the health sector, where women from minority ethnic and racial groups, including migrant women, can be disproportionately represented among lower status workers.)

On violence and harassment:

- Take action to protect women from online harassment and bullying, issues such as gender-based violence and workplace violence/harassment; and

- Support ratification and implementation of ILO Convention 190 on Violence and Harassment at work.

What recommendations would you have for FIP on supporting the provision of PPEs to women in pharmaceutical sciences and pharmacy education?

- Intentionally address power and privilege to enable a PPE grounded in equality and rights;

- Build the foundation for equality, ensuring equal pay for equal work and gender pay gap transparency;

- Instigate parental leave and family friendly policies;

- Provide clear guidelines against violence and sexual harassment at work;

- Address social norms and stereotypes (social norms and gender stereotypes drive much of the gendered segregation in the health and social workforce and the lower value placed on professions that are mostly female; gendered stereotypes of occupations and of leadership as a “man’s role” originate long before people join the workforce);

- Address workplace systems and culture (interventions in this area in the past have focused on training for women in areas such as self-esteem and self-presentation, on the assumption that women needed to change to compete in systems and cultures designed for men; this ignored the systemic inequality, bias and exercise of power that favoured men for leadership roles);

- Enable women to achieve by putting in place deliberate measures to enable women, who comprise the majority in the health and social care workforce, to apply for and achieve leadership positions equally and on merit; and

- Enable accountable leadership (leaders of all genders should be measured against targets on their performance on creating and enabling PPEs for women staff).

Reference

- BMJ. Men predominate in more than 85 percent of COVID-19 decision-making/advisory bodies globally. ScienceDaily. Available at: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/10/201001200244.htm. (Accessed 30 September 2021).

By Dr Belma Pehlivanovic, FIPWiSE Remote Volunteer; Lecturer, University of Sarajevo, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Key messages:

- Positive practice environments (PPEs) enable the recruitment and retention of employees, support the delivery of high-quality work outcomes, and benefit society as a whole.

- In order to achieve gender equality, it is necessary to provide equal treatments, rights, obligations and opportunities for all genders according to their needs.

- Lately, progress is being made to increase women’s involvement across different areas, however women are still underrepresented across the wider science, technology and education sector.

- Gender inequalities in the workplace are more than just statistics; they represent a huge challenge at local, national and global levels.

- In order to achieve equality in workplace environments, urgent actions are needed with continuous recognition and acknowledgment of women in pharmacy education and in the pharmaceutical science professions.

- Research shows that women and men are not provided with equal opportunities for career growth due to the fact that women receive less co-worker support and fewer opportunities for involvement in mentoring programmes, training and networking. Institutions and leading organisations should offer guidelines and strategies to promote fair treatment and equal opportunities which will result in the establishment of PPEs.

- Key factors for a PPE for women in science and education, and across the whole pharmaceutical workforce, are equal incentives for equal pay, work-life balance, creating supportive and safe working environments, opportunities for professional development, recognition and empowerment, and women in leadership.

Without a serious focus on the global health workforce crisis, a shortage of 18 million health workers is expected worldwide by 2030.1 Reasons for this are varied and complex, however, the main cause is a low quality of healthcare workplaces which leads to weakened health services and efficiency of health workers. Nowadays, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought us face to face with the importance of the need to ensure safe and purposeful practice environments for health professionals. In order to achieve health workers’ well-being and general safety, it is of crucial importance to establish PPEs across healthcare systems worldwide.1,2

In order to raise awareness and improve quality of workplaces for all health personnel, the World Health Professions Alliance (WHPA) has launched an initiative entitled “Stand up for positive practice environments”, in collaboration with its partner organisations: FIP, the World Dental Federation, the International Council of Nurses, World Physiotherapy and the World Medical Association. Throughout this initiative, a PPE has been defined as a healthcare setting that supports excellence, and decent work conditions, and has the power to attract and retain staff, provide quality care and deliver cost-effective, people-centred healthcare services. The factors identified by the WHPA to achieve PPEs are professional recognition, commitment to equal opportunities, investment in healthy and safe work environments and increased opportunities for professional training and career advancement. These lead to improved performance and professional self-worth of health professionals as well as their ability to remain healthy, motivated and efficient in their working environments. A PPE enables the recruitment and retention of employees, supports the delivery of high-quality work outcomes, and benefits society as a whole.2

The global tendency to develop a more cohesive and productive health workforce is based on establishment of gender equality in workplaces. The importance of gender equality is highlighted as one of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).3 In order to achieve gender equality, it is necessary to provide equal treatments, rights, obligations and opportunities for all genders according to their needs. By providing such treatments, gender equity is established as a leading means towards gender equality and improved socio-economic outcome for all genders.4 Implementation of gender equality in workplace environments results in improved organisational performance and reputation as well as increased national productivity and economic growth. Yet, gender inequalities occur often in different parts of health organisational structures, practices and education.5

Lately, progress is being made to increase women’s involvement across different areas; however, women are still underrepresented across the wider science, technology and education sector. Also, significant gender differences have been described throughout academic careers across science and technology, and there is evidence that women are publish fewer papers in all disciplines and in almost all countries. There are multiple forms of workplace gender inequalities that affect women’s position, empowerment and career advancement.6 These include the gender pay gap, shortage of women on leadership and decision-making positions, maternity discrimination and slower career progression opportunities. It has been suggested that some of the most harmful workplace gender inequalities for women are mediated throughout the practice and policies of human resources (HR) due to the fact that HR decisions affect payment, hiring, professional development and promotion.5

Nowadays, there are several programmes, initiatives and movements created to support equity, involvement and active participation of women in health, science and education. Significant activities towards gender equity in health are being made by the global movement Women in Global Health (WGH) which represents the largest network of women and allies in 90 countries, including low- and middle-income countries.7 A pioneering programme, founded by UNESCO and L’Oréal Corporate Foundation, seeks to promote women in science and recognise women researchers who have contributed to overcoming global challenges (L’Oréal-UNESCO for Women in Science Programme).8 One of FIP’s Development Goals (DG 10) is the global implementation of equity and equality in pharmaceutical workforce development and career progression opportunities.9 As a part of FIP’s EquityRx programme,9 FIP launched its FIPWiSE (Women in Science and Education) initiative on 11 February 2020 on the UN International Day of Women and Girls in Science, which aims to enable women to reach their fullest potential in fields of pharmaceutical science and education and to attract female students and young professionals into these fields,.10 There are number of national associations and organisations which support female health professionals and deal with issues of special relevance to female workers in science and education. In order to combat and decrease the gender gap in healthcare systems, a non-profit organisation, Women in Medicine, provides education, skills development and professional growth for women in this field.11 Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health is the professional community committed to increase diversity and equity in the nursing profession and provides women’s and gender-related health care.12 The National Association of Women Pharmacists — a network of the United Kingdom’s Pharmacists’ Defence Association — represents and supports female pharmacists.13 Due to the evident lack of women in leading positions across the pharmaceutical workforce in Pakistan, the National Alliance for Women in Pharmacy has launched an initiative under the Pakistan Pharmacist Association with the aim of attracting and empowering women in pharmacy as well promoting gender equity within Pakistan’s pharmaceutical profession.14

Women make up the majority of the global health workforce as well as most of the pharmaceutical workforce.15 FIP predicts that, by 2030, more than 70% of the pharmaceutical workforce worldwide will be women.16 Although men are being outnumbered in the global pharmacy workforce, women are still underrepresented in leadership roles and decision-making positions. This is considered a step backwards from establishing a gender equal working environment. Furthermore, direct discrimination against women in the pharmaceutical profession is seen through the gender pay gap as female professionals tend to be paid less and obtain lower-status positions than male professionals.15,17 Although there has been a significant increase in the number of women in pharmaceutical education appointed to the position of assistant or associate professor, there are fewer women who are appointed to the highest-ranked affiliations and higher academic leadership positions. Furthermore, it has been shown that a gender gap also occurs in the number of published papers, grant supports, recognition awards, speaker invitations and composition of editorial boards.15,18,19 Some of the most important means of assuring productivity and satisfaction of the workforce are opportunities for career advancement and professional development. Research shows that women and men are not provided with equal opportunities for career growth due to the fact that women receive less support from co-workers and fewer opportunities for involvement in mentoring programmes, training and networking. Institutions and leading organisations should offer guidelines and strategies to promote fair treatment and equal opportunities which will result in the establishment of PPEs.15,20

Nowadays, gender inequalities in the workplace are far from being just a statistical representation of imbalance between men and women; they represent a huge challenge at local, national and global levels. In order to achieve equality in workplace environments, urgent actions are needed with continuous recognition and acknowledgment of women in education and in pharmaceutical professions. It is of crucial importance to raise awareness of gender inequalities in the pharmaceutical workforce and, therefore, to develop strategies to improve gender equity and equality.1,15,21

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Health workforce. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-workforce#tab=tab_1. (Accessed 12 August 2021).

- World Health Professional Alliance (WHPA). Stand up for Positive Practice Environments. Available at: https://www.whpa.org/activities/positive-practice-environments. (Accessed 12 August 2021).

- UN Women. SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-and-the-sdgs/sdg-5-gender-equality. (Accessed 19 August 2021).

- Mencarini L. Gender Equity. In: Michalos A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht. (2014) Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1131. (Accessed 19 August 2021).

- Stamarski CS, Son Hing Sl. Gender inequalities in the workplace: the effects of organizational structures, processes, practices, and decision makers’ sexism. Frontiers in Pscyhology. 2015;6:1400. DOU: 10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1131.

- Huang J, Gates AJ, Sinatra R, et al. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020; 117 (9): 4609-4616. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1914221117.

- Women in Global Health (WGH). Gender Equal Health & Care Workforce Initiative. Available at: https://www.womeningh.org/. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). L'Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Programme. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/science-sustainable-future/women-in-science. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- The International Pharmaceutical Federation. FIP-equityRx collection. Inclusion for all. Equity for all. The Hague: FIP, 2019. Available at: https://www.fip.org/file/4391. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Women in Education and science initiative (WiSE). Available at: https://www.fip.org/fipwise. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- Women in Medicine (WIM). Available at: https://www.womeninmedicinesummit.org/. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH). Available at: https://www.npwh.org/. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- Pharmacist’ Defence Association (PDA). The National Association of Women Pharmacists (NAWP). Available at: https://www.the-pda.org/nawp-to-continue-as-part-of-the-pda/. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- Pakistan Pharmacist Association. Available at: https://ppapak.org.pk/. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

- Bukhari N, Manzoor M, Rasheed, H. et al. A step towards gender equity to strengthen the pharmaceutical workforce during COVID-19. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice. 2020;13:15. DOI: 10.1186/s40545-020-00215-5.

- Legraien L. Hard look’ at gender parity needed as pharmacy’s female workforce set to grow. Pharmacist. 2018; Retrieved from https://www.thepharmacist.co.uk/news/hard-look-at-gender-parity-needed-as-pharmacys-female-workforce-set-to-grow/. (Accessed 25 August 2021).

- Manzoor M, Thompson K. Delivered by women, led by men: a gender and equity analysis of the Global Health and Social Workforce. WHO Hum Resour Health Obs. 2019;(24). https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/health-observer24/en/. (Accessed 25 August 2021).

- Legraien L. Hard look’ at gender parity needed as pharmacy’s female workforce set to grow. Pharmacist. 2018; Retrieved from https://www.thepharmacist.co.uk/news/hard-look-at-gender-parity-needed-as-pharmacys-female-workforce-set-to-grow/. (Accessed 25 August 2021).

- American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy 2008-09 profile of pharmacy faculty. Available at: https://www.aacp.org/research/pharmacy-faculty-demographics-and-salaries. (Accessed 25 August 2021).

- Bader L, Bates I, John C. From workforce intelligence to workforce development: advancing the eastern Mediterranean pharmaceutical workforce for better health outcomes. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(9):899–904.

Chapter 2 delves deeper into the five key factors that have impact on positive practice environments (PPEs) for women in science and education (WiSE), namely:

- Factor 1 — Equal incentives for equal work;

- Factor 2 — Work-life balance;

- Factor 3 — Creating supportive and safe working environments;

- Factor 4 — Opportunities for professional development, recognition and empowerment; and

- Factor 5 —Women in leadership.

These factors were identified based on the WHPA’s PPE campaign, literature, and shared experiences by WiSE to cover all aspects that women face in their working environments. Each factor has at least one case study from WiSE around the world. In each case, we read about real-life experiences and insight into the importance of these factors in recruiting, rewarding and retaining women in the workforce.

By Dr Ecehan Balta, FIPWiSE working group member; senior advisor to the President, Turkish Pharmacists’ Association, Turkey

Key messages

- Incentives are important means of attracting, retaining, motivating, satisfying and improving the performance of employees.

- Gender inequalities in pay are often assessed through an indicator known as the gender pay gap. Although unequal pay for the same work is a very important and unjust practice, eliminating it is an important but not the only step in the process.

- The concept of work of equal value insists that the comparison should not be limited to the content of the work, but that job requirements, such as the level of skill, effort and responsibility, and working conditions be compared.

- Performing regular pay equity analysis, determining work of equal value, creating fair reward systems, promoting pay transparency and making industry wide comparisons are possible solutions to ensure equal incentives are provided for equal work of value.

General overview

Incentives are an important means of attracting, retaining, motivating, satisfying and improving the performance of employees. Incentives can be applied to groups, organisations and individuals and may vary according to the type of employer as well as each professional’s preferences and motivators. Incentives can be positive or negative (as in disincentives), tangible or intangible, and financial or non-financial.

Some examples for the financial incentives are:

- Salaries/wages

- Pensions

- Bonuses

- Insurance

- Allowances

- Fellowships

- Loans

- Tuition reimbursement

Some examples of non-financial incentives are:

- Safe and clean workplaces

- Vacation days

- Professional autonomy and empowerment

- Sustainable employment

- Flexibility in working time and job sharing

- Recognition of work

- Support for career development

- Supervision

- Coaching and mentoring structures

- Access to/support for training and education

- Planned career breaks, sabbaticals and study leave

- Occupational health and counselling services

- Recreational facilities

- Equal opportunity policies

- Enforced protection of pregnant women against discrimination

- Parental leave

A person’s gender is not an indicator of either talent or competence, and this simple truth must be a key component of diversity strategies that reflect the world we live in.

In general, positive discrimination policies have been included in the Constitution of Turkey. However, the implementation is limited and only applies to social services. In strategic areas where gender-based discrimination and inequalities persist, for example, at the management levels of public institutions, in local governments and in national parliaments, national action plans do not envisage transformative and affirmative action policies in order to increase the low participation rates of women.

One of the most important elements of International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention No. 100 is its insistence that the right to equal pay for equal work should not be confined to equal pay for the same or similar work, but should extend to work of equal value. The Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women has a similar provision in Article 11(d), which requires state parties to take all appropriate measures to ensure “the right to equal remuneration, including benefits, and to equal treatment in respect of work of equal value, as well as equality of treatment in the evaluation of the quality of work”.1

Gender inequalities in pay are often assessed through an indicator known as the gender pay gap. The gender pay gap measures the difference between male and female average earnings as a percentage of the male earnings.2 Overall, features such as differences in educational levels, qualifications, work experience, occupational category and hours worked account for the “explained” part of the gender pay gap. The remaining and more significant part, the “unexplained” portion of the pay gap, is attributable to the discrimination – conscious or unconscious – that is pervasive in workplaces.3 While the gap has been gradually closing over the past decades, there is still a substantial gender pay gap in many countries, ranging from a few per cent to over 40%.4

Although unequal pay for the same work is a very important and unjust practice, eliminating it is an important step, but not the only step, in the process. Where there is extensive job segregation, the problem is not that women are paid less for the same work, but that they are a “secondary workforce”, concentrated in undervalued, feminised work. The concept of work of equal value insists that the comparison should not be limited to the content of the work, but that job requirements, such as the level of skill, effort and responsibility, and working conditions be compared. In addition, it should be emphasized that there is a gender-based inequality in the acquisition of these skills by providing suitable environments and access to educational opportunities. For this reason, the lens of equality should also be used, especially in vocational training.

At the same time, care needs to be taken to ensure that the ways in which value is set do not replicate the assumptions that have always made men’s work appear more valuable. It is therefore essential that legislation should include means of assessing job values which are independent of the employer and existing arrangements, and should require the participation of affected women workers. There should also be the possibility of challenging job evaluation schemes on the basis that they are discriminatory on grounds of gender.

Perspective on science and education and impact on the profession

Working in the healthcare field requires, first, a certain freedom of movement and freedom to use time. Issues such as having to work in a city other than the one you live in, compulsory service periods and night shifts may cause a person to choose a profession according to their gender. The education of health professions, in our case the pharmaceutical workforce, is longer compared with other undergraduate education and vocational trainings. These features are criteria to be considered when choosing a field of undergraduate education. Women prefer or are forced to choose jobs that are an extension of their care processes. The hierarchy of health professions is established accordingly. Medical doctors are at the top of the hierarchy, and they also carry certain hierarchies according to their specialties. In the formation of this hierarchy, it is of great importance that the jobs preferred by women are cheaper and less supported, even if they are more difficult, due to general social discrimination. For this reason, it is extremely important to encourage women and to activate some incentives such as scholarships at the training stage, especially for the branches that appear at the top hierarchically.

Currently, there has been no gender-lensed regulation in my workplace. In parallel, gender equality is not included as a basic norm in the Turkish government’s official documents or national action plans, especially since 2018.1 In addition, many official documents do not mention the protection of women’s rights and compliance with the norms of equality between men and women. In the national policies and political and legal documents of the relevant institutions, the norms of “protection and strengthening of the family” and “protection of national and moral values” are included instead of the norms of the protection of women’s rights, or gender equality.

Suggested actions

- Perform regular pay equity analysis: Companies and institutions can identify gendered pay differences within the organisation — at different levels and in different functions — by gathering comprehensive pay data and performing thorough pay equity analyses. The results of these reviews are critical to gain insights into prevalent pay gaps in the workplace. To achieve and maintain pay equity, the determinants of the wages of women and men in workplaces should be analysed, and whether gender is a factor should be regularly tested on a workplace basis.

- Determine equal value: It is important for workplaces to independently assess the value of each job and ensure that the process is free from bias. The ILO guide “Promoting equity: Gender-neutral job evaluation for equal pay” is an effective tool to compare jobs and determine the value of a job in relation to others. Companies should use the analytical job evaluation method to determine the numerical value of the job based on a range of gender-neutral criteria, including skills and qualifications, responsibilities, effort and working conditions, and ensure equal remuneration for work of equal value. In this way, companies can make sure that jobs held predominantly by women are not undervalued or underpaid.

- Create a fair reward system: Lack of transparency in structuring compensation or reward packages can worsen the pay disparity between men and women. Setting clear and objective criteria to determine reward helps companies check for bias in the pay and promotion process. Companies can tackle the pay gap in compensation systems by setting a threshold, target and maximum for pay increases or bonuses to ensure equitable, merit-based reward distribution among men and women.

- Promote pay transparency: Achieving pay equity at work requires greater pay transparency. For example, to promote income transparency, the Austrian National Action Plan for Gender Equality in the Labour Market has made it mandatory for all companies with more than 150 employees to publish staff income reports every two years. Companies are required to report the number of men and women classified under each category along with the average or median income for the respective category.

- Make industry-wide comparisons: Industry-wide comparisons should be used, particularly in sectors in which collective bargaining operates at sectoral level. It is known that all kinds of discrimination, including discrimination based on gender, reduce the motivation of employees who are discriminated against. At the same time, these discriminations also affect those who benefit from health services and can act as a way of reducing their feelings of trust towards the service providers. Ranking of health professions by gender also affects the wages received for nursing and nursing services, for example, in which mostly women work. Such a perception of people’s jobs will affect the quality of the job, the expectation from the job, and the future of the job.

Good practice examples and case studies

As an example of performing regular pay equity analysis, Microsoft adopted several measurable diversity goals to ensure that there is “not only equal pay for equal work but also equal opportunity for equal work”. Microsoft has established pay monitoring systems and qualitative scorecard data reviews to ensure that no salary discrepancies arise. Microsoft’s base pay among women and men of all races in the United States varies by less than 0.5%.4

For creating a fair reward system, Google’s initiative could be held up as a good practice intervention. It has promoted gender diversity by encouraging women to negotiate. The Google analytics system identified its reward model, based on self-nomination, as a major barrier resulting in fewer women being promoted. Fewer women advocated for themselves as they often encountered pushback. To address this issue, Google organised workshops for its female leaders stressing that they were expected to self-promote and highlighting strategies to do so. As a result, Google has successfully closed the gender gap in promotions.6

For developing career opportunities for women, the case of Griffith University, Queensland, Australia, is another good practice intervention. To address a persistent gender imbalance in senior management roles, Griffith University has been working to increase the number of women entering leadership roles by developing the leadership skills of existing staff.8,9

- Fredman S. Background Paper For The World Development Report 2013 Anti-discrimination laws and work in the developing world: A thematic overview; S. Fredman Literature Review on the Enforcement of ILO Convention 100: Report prepared for the ILO and the South African Government Feb 2013. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/documents/issues/women/wg/esl/backgroundpaper2.doc. (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- Oelz, M., Olney, S. and Tomei, M. (2013). Equal pay: An introductory guide. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- International Labour Organization, (2015). Global Wage Report 2014/15. Geneva. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/global-wage-report/2014/lang--en/index.htm. (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- International Labour Organization (ILO), 2021, Pay Equity A Key Driver Of Gender Equality, Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@gender/documents/briefingnote/wcms_410196.pdf. (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- Sürdürülebilir Kalkınma Derneği (SKD) Türkiye (2021), “Eğitim ve İşgücünde Kadın Oranı Azalıyor”. Available at: http://www.skdturkiye.org/esit-adimlar/yakin-plan/egitim-ve-isgucundeki-kadin-orani-azaliyor. (Accessed 9 September 2021).

- Pay Equity Office (PEO) (2019), A Guide to Interpreting Ontario’s Pay Equity Act. Available at: http://www.payequity.gov.on.ca/en/DocsEN/2019-01-31%20Pay%20Equity%20Office%20Guide%20to%20the%20Act%202019%20-%20EN.pdf. (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- Williams J. Hacking Tech’s Diversity Problem. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/10/hacking-techs-diversity-problem. (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), Case Study: Developing Women Leaders. Available at: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/WGEA-Griffith-Uni.pdf. (Accessed 7 September 2021).

- Australian Government: Workplace Gender Equality Agency, Case studies: Research showcasing leading practice in two organisations. https://www.wgea.gov.au/case-studies. (Accessed 21 August 2021).

By Dr Dalal Hammoudi Halat, FIPWiSE working group member, School of Pharmacy, Lebanese International University, Lebanon

Key messages

- Work-life balance is not the allocation of time equally among work, family and private life, but rather prioritising and distributing the available resources like time, thought and labour wisely among them.

- Society has double expectations for women. On one hand, women are expected to actively participate in work and contribute to the society at various levels; on the other hand, women are expected to play a substantive family role.

- Work-life balance improved productivity and increased organisational commitment, while allowing better apparent control over responsibilities outside work.

General overview

Researchers and executives alike have a growing interest in work-life balance, and it constitutes a concern for both men and women with professional careers.1 By definition, work-life balance is an individual’s ability to meet their work and family commitments, as well as other non-work responsibilities, activities, and roles in different life sectors, in addition to the relations between work and family obligations. It may be additionally defined as satisfaction and proper functioning at work and home with minimum role conflict.2 In a more applicable aspect, work-life balance implies being able to satisfactorily fulfil the demands of three basic areas: work, family and private life. Work-life balance is not the allocation of time equally among these areas; rather, it is prioritising and distributing available resources like time, thought, and labour wisely among them.3 Simply stated, work-life balance is a concept that is both complex to define and difficult to achieve.4

Nowadays, work-life balance seems hard to achieve, with fears over job losses and advances in technology that have made workers accessible round the clock. However, compounding stress from a never-ending workday is damaging, and can seriously hurt relationships, health and happiness, ultimately resulting in burnout, which manifests as atypical behavior.5 Poor work-life balance was positively associated with poor health outcomes such as fatigue, mental health issues, sickness, absenteeism, musculoskeletal diseases, and work-related risks on health and safety.6 These adversities can partly be explained by multiple roles and overload of demands and responsibilities among working adults.7 The gendered realities of work-life balance, in particular the division of unpaid labour, such as childcare and household chores, were revealed and exaggerated towards women during the unprecedented time of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated lockdowns.8,9 As such, it is imperative that women in science and education develop a better integration of work and life. This factor of our toolkit will aim to enhance the understanding of work-life balance for women in science and education, and formulate suggestions for better life satisfaction.

Perspective on science and education

Society has double expectations for women. On one hand, women are expected to actively participate in work and contribute to society at various levels; on the other hand, women are expected to play a substantial family role. Studies have shown that women are always more stressed than men, particularly women working full-time whose children are under 13 years old, with most common stresses being from family, work and the economy.10 In itself, this forms a major challenge for all women, but also for those in science and education, leading to the deviation between employment expectations and actual employment selections. This makes women often suffer from mental disturbances and struggles, and results in an overall decrease in women’s personal well-being.

Women in scientific careers are constrained by conflicts between the normative demands of family and scientific research that calls for long working hours and frequent scientific mobility. This results in poor work-life balance, marital relationship and family suffering, and prejudice for women who choose to establish career over marriage. Some women scientists face constrained social norms that exert pressure on them to get married and have children, while their peers are establishing their science careers. Women scientists also experience inequitable structures of gendered support systems within institutions, with insufficient mentoring, lack of psychosocial support, lack of formal provision of flexible working time, under-representation in scientific leadership and decision-making bodies, and limited ability to strike a balance between family life and career.11

However, the old culture of “breadwinning men and homemaking women” and “farming men and weaving women”, the traditional patterns of gender partition of labour, have changed, and women’s social roles have shifted from a single role of family to a dual role of family and career.11

Impact on the profession

A scientific foundation for strategies of work-life balance should help women in science and education to improve their experiences and realise a positive change in their workplaces as well as in their personal lives. The key recommendations for such positive actions depend on both individuals and institutions.

Starting with individual strategies, a personal viewpoint on work-life balance tips has been nicely presented by Mattock.4 Generally speaking, there is no “magic formula” for women to achieve work-life balance; rather, they should evaluate their status quo, and take steps to improve balance in their daily routine. Among others, some useful tips may be building downtime in the person’s calendar for family events, personal appointments, or simply “busy” time when one desires to remain uninterrupted to finish delayed or postponed tasks. Other strategies are to drop off activities that consume time and energy, to purposefully and reasonably schedule errands to increase quality time with family, to get enough physical exercise and meditation, to unplug from work responsibilities by avoiding telecommunications during family time, and to earn time off, like leave or vacations, which are well deserved by individuals and their families. Furthermore, women overachievers develop perfectionist tendencies at younger age when obligations are limited to school, hobbies and maybe a part-time job. As life gets more complicated, with greater family burden and amplified work responsibilities, perfectionism becomes beyond reach, and with that habit left unrestrained, it can become destructive.12

At an institutional level, in 2021 Liani11 outlined a group of key approaches for a positive work-life balance collected from female researchers themselves. These approaches can be summarised as follows:

- Institutions should commit to supportive and gender-sensitive work environments, where standard operating procedures formally prevent discrimination and promote gender equity.

- Institutions should promote family-friendly policies and practices regarding caregiving obligations and child-care support, such as mother/baby friendly lactation rooms. Also, a culture of female encouragement should be cultivated, for instance, by declaring that “female candidates are highly encouraged to apply”.

- Institutions should nurture a supportive research environment whereby female researchers can discuss and provide mutual support around career challenges, career decisions and work-life balance issues. The availability of occupational therapists and counsellors at the workplace to handle psychological issues experienced by female researchers is, indeed, an added value.

- Women should be better represented in senior scientific and leadership appointments to help enhance gender equitable decision-making. A mindset change around dealing with social norms, values and expectations shall help women in science and education to build confidence and resilience.

- Public awareness should be raised about researchers’ work, particularly about the nature of research that requires years of hard work and frequent mobility, for which women researchers tend to be more deprived based on reproductive gender roles compared with men.

Further, a report13 on positive practice environments published by the World Health Professions Alliance considers work-life balance essential to keep employees safe, healthy, motivated and productive. The report outlines an armamentarium of financial (wages, insurance, housing, etc.) and non-financial (vacation, recreational activities, supervision, coaching, flexible working hours, etc.) incentives that support professionals and help attract and retain employees.

According to literature, work-life balance positively and significantly affects employee performance.14 Researchers around the globe, who have been hard at work studying and surveying the issue of work-life balance and productivity for decades, have found that work-life balance improved productivity and increased organisational commitment, while allowing better apparent control over responsibilities outside work.15 For women, the ability to develop their unique leadership identity and successfully address their career growth is fostered when they experience supportive environments and are offered opportunities to balance their diverse obligations of work and family.16

Suggested actions

According to a recent public health report in 2020,17 governments, organisations and policy makers should provide favourable working conditions and social policies for working adults to deal with competing demands from work and family activities. As such, the agenda of executives in charge of pharmacy schools, research institutions, and national bodies should focus on a family-friendly organisational culture and resources, such as:2,18

- Flexible working hours and flexible deadlines;

- Childcare schemes (such as nurseries) and elderly care schemes;

- Maternity, paternity, and special leave;

- Working from home, away from traditional working environments;

- Job sharing;

- Supportive programmes for the family life of employees; and

- Revised labour laws to prevent excessive working hours.

Finally, perhaps the first step in building a culture that supports work-life balance is to talk about it. Discussions can take place at an executive level, in focus group meetings, or on a one-to-one basis such as performance reviews.19,20 Such prompts shall help support both women and men in education and science to overcome challenges around work-life balance, and avoid feelings of guilt from having to attend to a family obligation or personal emergency. Overall, these prompts shall contribute towards a better positive environment in the workplace.

Good practice examples: A case study

According to Harvard Business Review,21 in a study of about 300 business professionals who spent less time on work and more on other aspects of their lives, satisfaction increased by average of 20% in work, 28% in home, and 31% in the community. Perhaps the most significant finding was satisfaction in the domain of physical and emotional health and intellectual and spiritual growth, which increased by 39%, together with improved performance at work (by 9%), at home (15%), in the community (12%), and personally (25%). Participants were working more agiler, and were more focused, passionate, and committed.

- Wong K, Chan AHS, Teh P-L. How is work-life balance arrangement associated with organisational performance? A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):E4446.

- Delecta P. Work life balance. International Journal of Current Research, 2011;3(4):186-189.

- Wilcox J. Work-life balance. Heart. 2020;106(16):1276-1277.

- Mattock SL. Leadership and work-Life balance. J Trauma Nurs. 2015;22(6):306-307.

- Bajaj AK. Work/life balance: It is just plain hard. Ann Plast Surg. 2018;80(5S Suppl 5):S245-S246.

- Choi E, Kim J. The association between work-life balance and health status among Korean workers. Work. 2017;58(4):509-517.

- Lundberg U, Mårdberg B, Frankenhaeuser M. The total workload of male and female white collar workers as related to age, occupational level, and number of children. Scand J Psychol. 1994;35(4):315-327.

- Hjálmsdóttir A, Bjarnadóttir VS. “I have turned into a foreman here at home.” Families and work-life balance in times of COVID-19 in a gender equality paradise. Gend Work Organ. Published online September 19, 2020.

- Yerkes MA, André SCH, Besamusca JW, et al. “Intelligent” lockdown, intelligent effects? Results from a survey on gender (in)equality in paid work, the division of childcare and household work, and quality of life among parents in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242249.

- Shui Y, Xu D, Liu Y, Liu S. Work-family balance and the subjective well-being of rural women in Sichuan, China. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):1.

- Barriers and enablers for enhancing career progression of women in science careers in Africa. Available at: https://www.ukcdr.org.uk/blog-millicent-liani-barriers-and-enablers-for-enhancing-career-progression-of-women-in-science-careers/. (Accessed 13 August 2021).

- Lee DJ. Six Tips For Better Work-Life Balance, Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/deborahlee/2014/10/20/6-tips-for-better-work-life-balance/. (Accessed 13 August 2021).

- Stand up for Positive Practice Environments | World Health Professions Alliance. Available at: https://www.whpa.org/activities/positive-practice-environments. (Accessed 13 August 2021).

- Bataineh K. Impact of work-life balance, happiness at work, on employee performance. International Business Research. 2019;12:99.

- Robinson J. Work-Life Balance Research. Available at: https://www.worktolive.info/work-life-balance-research. (Accessed 13 August 2021).

- Brue KL, Brue SA. Leadership role identity construction in women’s leadership development programs. Journal of Leadership Education. 2018;17(1):7-27.

- Mensah A, Adjei NK. Work-life balance and self-reported health among working adults in Europe: A gender and welfare state regime comparative analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1052.

- Hsu Y-Y, Bai C-H, Yang C-M, et al. Long hours’ effects on work-life balance and satisfaction. BioMed Research International. 2019;2019:e5046934.

- CVCheck. What work-life balance really looks like for women in 2020 - Checkpoint. Available at: https://checkpoint.cvcheck.com/. (Accessed 13 August 2021).

- CVCheck. What work-life balance really looks like for women in 2020 - Checkpoint. Available at: https://checkpoint.cvcheck.com/what-work-life-balance-really-looks-like-for-women-in-2020/. (Accessed 13 August 2021).

- Friedman SD. Be a better leader, have a richer life. Harvard Business Review. Published online April 1, 2008. Available at: https://hbr.org/2008/04/be-a-better-leader-have-a-richer-life. (Accessed 13 August 2021).

Factor 2. Case study 1

Author not disclosed

Could you briefly comment on what kind of inequalities you have experienced or observed in your workplace/organisation regarding work-life balance in education and science?

In Denmark we are very fortunate regarding equity. Denmark has had since the 1970s established structures to assist childcare and care for the elderly, which gives women the opportunity to pursue their own professional goals and a career. In Denmark we have what is called the “frame for work”. The frame for work is negotiated between unions and employers every two to three years and is therefore not set by the government. Only if the two parties cannot come to an understanding will the government step in. Equity, including work-life balance, has been a point of agreement over the years, and maternity leave and care leave will typically be part of the agreement.

Therefore, the structure is established in Denmark. Implementation within the frame of work is to be decided by individual families, and here we still see that it is primarily women who take different care leaves and ask for a reduction in hours per week.

At universities and major companies, there is still debate about the existence of a glass ceiling, and the top leadership positions in many places are occupied by men.

Could you briefly comment on what kind of policies and actions you have in your workplace/organisation for work-life balance in education and science?

In my workplaces, we have an agreement regarding our academic employees. In this we uphold and encourage the opportunity for both women and men to take maternity/paternity leave and care leave. We see that many women choose to reduce their working hours for a longer or shorter time in their life.

Have you experienced or observed any practice that has been implemented in the workplace during the COVID-19 pandemic that has caused gender inequality in work-life balance?

The greatest change regarding work-life balance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark has been that all employees have been working from home for short or long periods. For some this has been welcomed and flexible; for others it has been a deprivation and they have greatly missed their daily interaction with colleagues. It has been the same for both genders. Due to this we will be talking about how we in the future can use working from home as a tool in solving our tasks at work.

Where should we start to establish work-life balance in education and science workplaces?

I think there are two points we should address: (i) making equal opportunities to pursue one’s goal and ambition from a structural perspective (employer); and (ii) taking opportunities to pursue one’s goals and ambition from an individual perspective (employee). In practice, for me, this means that allocation of opportunities and positions should be based on qualifications and never on gender. And as an employee you should also be conscious about what you are willing to invest in your own career and what you want to achieve.

Which organisations (global, regional or national level) can support us on the initiatives for equal pay for work-life balance in education and science in the workplace?

I have heard of internationally acknowledged universities only giving permanent employment to men, and women are aged in their 40s before they can get a permanent position. This is wrong. Therefore, I think that FIP is actually a strong platform to start this dialogue, because FIP has member organisations that are policy makers in this area, e.g., national unions, national branch organisations, and universities and schools of pharmacy. On the international level, the UN could be a platform. Both the UN Sustainable Development Goals and work under UNICEF target equity.

Factor 2. Case study 2

By Ning Wei Tracy Chean, Regulatory Affairs, Quality Assurance and Pharmacovigilance Manager, Galderma SEA, and Wing Lam Chung, Principal Clinical Pharmacist, Watson’s Personal Care Stores Pte Ltd, Singapore

Wing Lam Chung’s case study is shared in this toolkit to provide a wider perspective from the pharmaceutical workforce.

Could you briefly comment on what kind of inequalities you have experienced or observed in your workplace/organisation regarding work-life balance in education and science?

Ms Chean: In my organisation and industry, the majority of employees are female. I have had the blessing to not experience inequalities and I believe this is due to the leadership team’s effort to ensure all genders are treated with utmost respect. The support provided to women throughout the milestones in both their professional career and personal life is apparent. Women’s opportunities for further education to upskill are not impacted in any way, and if they decide to focus more on their family, it is solely based on their personal choice.